We treat more back pain than any other complaint, split about evenly between upper and lower back pain. Additionally, most of the people we see whose chief complaint is low back pain (LBP) also often concede that they have some upper back pain (UBP) as well – and vice versa.

We treat more back pain than any other complaint, split about evenly between upper and lower back pain. Additionally, most of the people we see whose chief complaint is low back pain (LBP) also often concede that they have some upper back pain (UBP) as well – and vice versa.

So what do your head and neck have to do with it?

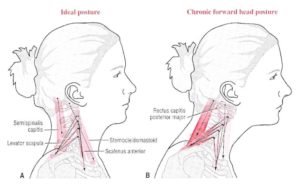

There is clear a correlation between low back problems and neck problems. Many causes have been suggested for this, but one of them seems obvious – most people have allowed their head to drift out in front of their body. In many cases the shoulders also round as the head moves forward, rounding the upper spine into a condition called kyphosis.

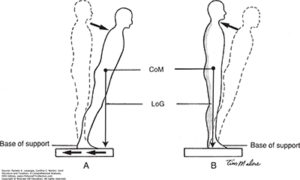

If our head is too far forward the weight of the head, neck and shoulders puts our Center of Mass(CoM) out in front of our Base of Support (BOS).

If our head is too far forward the weight of the head, neck and shoulders puts our Center of Mass(CoM) out in front of our Base of Support (BOS).

When our CoM is over our BoS the Line of Gravity (LoG) drives straight down through our spine and leg bones.

When the CoM is out in front of the BoS the LoG pulls us forward. If we didn't do something to allow for it we would fall.

When the CoM is out in front of the BoS the LoG pulls us forward. If we didn't do something to allow for it we would fall.

This is what happens when our head is forward in front of our body - a condition that is all too common these days. There are two common bad strategies we might use to try to move our CoM back over our BoS :

- Pull the shoulders back while attempting to keep the lower back flat (Military or Flat Back posture). This puts chronic load on the upper back muscles and increases UBP or...

- Extend the lumbar spine to pull the chest head and shoulders back over the BoS (Lordotic posture). This loads the spinal erectors and can lead to LBP. In many cases the rounding of the shoulders persists as well and result is known as Kyphotic-Lordotic posture.

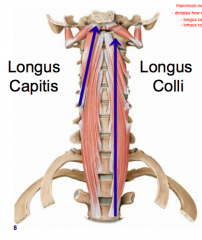

Although there are many factors to consider when trying to improve posture, a better strategy here is to focus on moving the CoM of your head back over your body. To accomplish this, we want to strengthen the Deep Cervical Flexors - muscles that are buried deep in the front of your neck, behind your esophagus and windpipe. They are called longus colli and longus capitis. They work together with the muscles in the back of the neck to center your head and neck over your spine.

Although there are many factors to consider when trying to improve posture, a better strategy here is to focus on moving the CoM of your head back over your body. To accomplish this, we want to strengthen the Deep Cervical Flexors - muscles that are buried deep in the front of your neck, behind your esophagus and windpipe. They are called longus colli and longus capitis. They work together with the muscles in the back of the neck to center your head and neck over your spine.

We recommend starting with a truly easy exercise that can be done laying down, seated or standing against a wall. We recommend laying down at first so that you can keep the rest of your spine straight and relaxed.

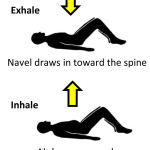

As with most of our self-care activities, we begin with the foundation of a good diaphragmatic breathing. Bring your attention to your breath and the combination of your diaphragm pulling down to allow air in and your transversus abdominis bracing against it.

We recommend starting with a truly easy exercise that can be done laying down, seated or standing against a wall. We recommend laying down at first so that you can keep the rest of your spine straight and relaxed.

As with most of our self-care activities, we begin with the foundation of a good diaphragmatic breathing. Bring your attention to your breath and the combination of your diaphragm pulling down to allow air in and your transversus abdominis bracing against it.

Neck Retraction With Chin Tuck

To initiate this movement, begin with slightly tucking the chin, then push your head straight back (down in this position) into the floor. Hold for one count. Check in with your lower and upper back - did you use those muscles too? Try again and make a conscious effort to use only your neck and avoid using your back muscles to assist. Hold the position for two counts and then a third time for three counts. Don't forget to breathe.

Check in with your lower and upper back - did you use those muscles too? Try again and make a conscious effort to use only your neck and avoid using your back muscles to assist. Hold the position for two counts and then a third time for three counts. Don't forget to breathe.

Building Strength and Stamina

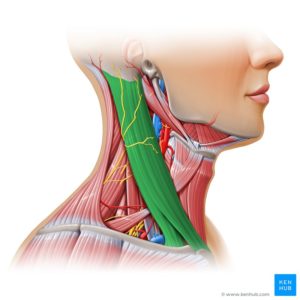

Neck muscles are pretty delicate, so we are going to stop there. Over successive days you should increase the number of repetitions to from 3 to 10, increasing the hold time for each from 3-10 counts as well. Don't forget to breathe. Ultimately, 10 seconds, plus 9+8+7, etc. adds up to a pretty substantial exercise We are using repetitions to build strength and holding the position to build endurance. After all, these muscles help keep your head over your body all day! It may not seem like a worthwhile exercise, but strengthening cervical flexors reduces pain! It is worth the effort. When your deep cervical flexors become injured or inhibited, the Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle can step in to help. Unfortunately, SCM is not designed to flex our neck. Its primary purpose is to act as a ‘check rein’ during sudden neck movements. It prevents us from hyper-extending our neck. However, we can see that the orientation of this muscle means that it also pulls our head and neck forward when we use it to flex our neck.

When your deep cervical flexors become injured or inhibited, the Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle can step in to help. Unfortunately, SCM is not designed to flex our neck. Its primary purpose is to act as a ‘check rein’ during sudden neck movements. It prevents us from hyper-extending our neck. However, we can see that the orientation of this muscle means that it also pulls our head and neck forward when we use it to flex our neck.

The first step in self-care of the SCM is to perform some gentle self-compression. You can do this more easily by turning to the side you are working on and tucking your chin slightly. This action creates some slack in the muscle.

The first step in self-care of the SCM is to perform some gentle self-compression. You can do this more easily by turning to the side you are working on and tucking your chin slightly. This action creates some slack in the muscle.

Then, gently massage the entire length of the SCM using your thumb and knuckle of your forefinger. If you find a tender area, pause and gently work a little more deeply. As you turn away, as in the photo, you will ‘lose’ the muscle and have only skin in your grasp.

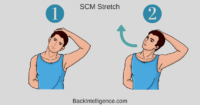

You should approach neck stretches with care. However, the basic idea of a healthy SCM stretch is to:

You should approach neck stretches with care. However, the basic idea of a healthy SCM stretch is to:

1) stabilize your arm and shoulder

2) gently turn away from the side you are stretching

3) gently extend the neck back

If you have sustained a neck injury such as whiplash, please contact us for more information.

Extra – Anatomy of Anterior Neck Muscles

The primary flexor of your neck is a muscle called Longus Colli - Latin for long muscle of the neck. Its partner Longus Capitis is the muscle that tilts your head down, as in a nod. They are also called Deep Cervical Flexors. These muscles are located deep in the neck, behind the esophagus and windpipe.

An accident, such as whiplash, can injure these cervical flexors and inhibit them. Inhibited muscles don't function properly. When this happens, other related muscles step in to help.

The most common helpers are the SCM (Sterno-Cleido Mastoid) – plainly visible as “cords” in the front of the necks of some people. Other neck flexors, such as your scalenes, are not easy to see. When the SCM or scalenes are chronically engaged, they cause pain. They also prevent the deep cervical flexors from recovering and doing their job.

The primary flexor of your neck is a muscle called Longus Colli - Latin for long muscle of the neck. Its partner Longus Capitis is the muscle that tilts your head down, as in a nod. They are also called Deep Cervical Flexors. These muscles are located deep in the neck, behind the esophagus and windpipe.

An accident, such as whiplash, can injure these cervical flexors and inhibit them. Inhibited muscles don't function properly. When this happens, other related muscles step in to help.

The most common helpers are the SCM (Sterno-Cleido Mastoid) – plainly visible as “cords” in the front of the necks of some people. Other neck flexors, such as your scalenes, are not easy to see. When the SCM or scalenes are chronically engaged, they cause pain. They also prevent the deep cervical flexors from recovering and doing their job.

Structure

The Longus colli is situated on the anterior surface of the upper vertrabrae between the atlas and the third thoracic vertebra. It is broad in the middle, narrow and pointed at either end, and consists of three portions, a superior oblique, an inferior oblique, and a vertical.- The superior oblique portion arises from the transverse processes of the third, fourth, and fifth cervical vertebræ and, ascending obliquely with a medial inclination, is inserted by a narrow tendon into the anterior arch of the atlas.

- The inferior oblique portion, the smallest part of the muscle, arises from the front of the bodies of the first two or three thoracic vertebræ; and, ascending obliquely in a lateral direction, is inserted into the transverse processes of the fifth and sixth cervical vertebræ.

- The vertical portion arises, below, from the front of the bodies of the upper three thoracic and lower three cervical vertebræ, and is inserted into the front of the bodies of the second, third, and fourth cervical vertebræ.

It isn’t apparent at first, but the deep cervical flexors help retract and centrate your head over the cervical spine and your neck over your thoracic spine. In contrast, helper muscles such as the SCM and scalenes, pull the head forward.

Strengthening your Deep Cervical Flexors helps restore balance in your neck and shoulder girdle. It reduces pain in the neck, shoulders and upper and lower back. Strengthening them is a vital part of any neck, shoulder or upper back rehabilitation program.

Significance

It is commonly injured in rear end whiplash injuries, usually resulting from a car crash.

This muscle is in front of the spine and is thought by some scientists that it may cause some whiplash patients to have an unnatural lack of curvature in the patients’ neck.

Acute calcific tendinitis of the longus colli muscle can occur. This presents with acute onset of neck pain, stiffness, and difficulty and pain with swallowing. Imaging diagnosis is by CT or MRI, demonstrating calcification in the muscle in addition to retropharyngeal oedema. Treatment is supportive, with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is one of the largest and most superficial cervical muscles. The primary actions of the muscle are rotation of the head to the opposite side and flexion of the neck. The sternocleidomastoid is innervated by the accessory nerve.

It is given the name sternocleidomastoid because it originates from the top of the sternum (sterno-) and the clavicle (cleido-), and has an insertion at the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the skull.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is one of the largest and most superficial cervical muscles. The primary actions of the muscle are rotation of the head to the opposite side and flexion of the neck. The sternocleidomastoid is innervated by the accessory nerve.

It is given the name sternocleidomastoid because it originates from the top of the sternum (sterno-) and the clavicle (cleido-), and has an insertion at the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the skull.