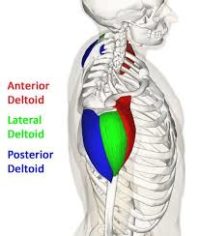

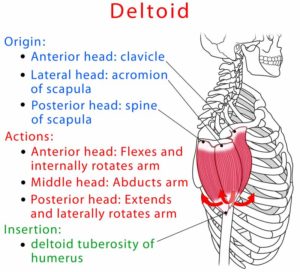

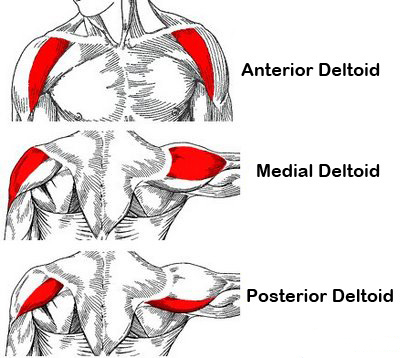

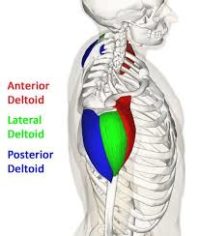

The deltoid is sometimes considered one muscle with three sections and sometimes treated as three separate muscles.

The deltoid is sometimes considered one muscle with three sections and sometimes treated as three separate muscles.

Together they form the bulk of your shoulder and are used to raise your arm from your side and flex and extend your arm at the shoulder.

Problems with the deltoid muscles are typically either related to underlying dysfunction in the rotator cuff muscles, chronic overload of the muscles from poor ergnomics and sports activities, or impact trauma to your shoulder.

The relationship between the deltoids and the rotator cuff muscles, especially supraspinatus, is just being fully understood.

Deltoid trigger points are often misdiagnosed as rotator cuff tears, bicipital (biceps) tendonitis, subdeltoid bursitis, subacromial impingment syndrome or C5 radicular pain.

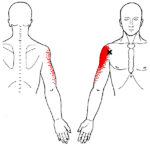

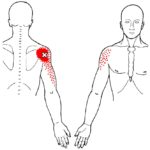

Symptoms of in the deltoid muscles vary from front to back.

Symptoms of in the deltoid muscles vary from front to back.

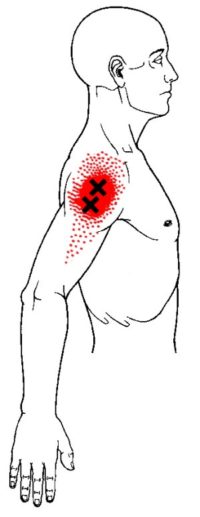

Active trigger points in the anterior deltoid most often refer into the front of your shoulder and down the front your upper arm.

Active trigger points in the anterior deltoid most often refer into the front of your shoulder and down the front your upper arm.

Trigger points in the middle deltoid refer localized pain to the outside of your shoulder. They are less likely to spread down your arm.

Trigger points in the middle deltoid refer localized pain to the outside of your shoulder. They are less likely to spread down your arm.

In the posterior deltoid, active trigger points are more likely to refer to the back of your shoulder and down the back of your upper arm.

Considering the function of the deltoid in abduction, if there is no obvious trauma to the deltoids, active trigger points suggest dysfunction in the rotator cuff muscles, especially supraspinatus.

However, trigger points in the deltoids often develop after a significant blow to the shoulder during contact sports, a fall or other accident.

In the posterior deltoid, active trigger points are more likely to refer to the back of your shoulder and down the back of your upper arm.

Considering the function of the deltoid in abduction, if there is no obvious trauma to the deltoids, active trigger points suggest dysfunction in the rotator cuff muscles, especially supraspinatus.

However, trigger points in the deltoids often develop after a significant blow to the shoulder during contact sports, a fall or other accident.

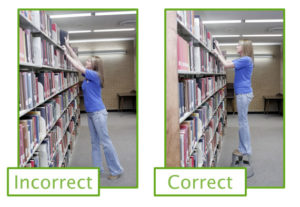

Trigger points in your deltoids can develop from cumulative stress of repeated lifting of your arms. This can can more strenous overhead lifting or something as simple improper postures and furniture for office and desk workers.

Deltoid pain is typically deep in your shoulder with motion and sometimes also at rest. If you have anterior deltoid trigger points you may have difficulty raising your arm or reaching behind your body at shoulder level. Trigger points in multiple deltoid muscle segments can cause almost total inability to raise your arm with weakness and pain.

Trigger points in your deltoids can develop from cumulative stress of repeated lifting of your arms. This can can more strenous overhead lifting or something as simple improper postures and furniture for office and desk workers.

Deltoid pain is typically deep in your shoulder with motion and sometimes also at rest. If you have anterior deltoid trigger points you may have difficulty raising your arm or reaching behind your body at shoulder level. Trigger points in multiple deltoid muscle segments can cause almost total inability to raise your arm with weakness and pain.

When a posture or activity that activates a trigger point is not corrected, it can also perpetuate it. Trigger points can be activated anywhere in the supraspinatus from unaccustomed eccentric loading, eccentric exercise in an unconditioned muscle, maximal or sub-maximal concentric loading.

Placing the muscle in a shortened or lengthened position for an extended period of time can also activate trigger points in the supraspinatus.

Trauma often causes trigger points in the deltoids. The muscles can be overloaded from swimming, overhead throwing, tennis, weight lifting, cross-fit and skiing, to name several common activities.

When a posture or activity that activates a trigger point is not corrected, it can also perpetuate it. Trigger points can be activated anywhere in the supraspinatus from unaccustomed eccentric loading, eccentric exercise in an unconditioned muscle, maximal or sub-maximal concentric loading.

Placing the muscle in a shortened or lengthened position for an extended period of time can also activate trigger points in the supraspinatus.

Trauma often causes trigger points in the deltoids. The muscles can be overloaded from swimming, overhead throwing, tennis, weight lifting, cross-fit and skiing, to name several common activities.  It is often the forceful flexion of your arm at the shoulder required in these activities that overloads the deltoids.

Trauma from the impact of contact sports to being hit by baseball, tennis ball or golf ball, can activate deltoid trigger points.

If you slip on the stairs to the effort of suddenly reaching for the handrail can activate trigger points in your deltoids. Consider gently maintaining contact with the rail as you walk up and down stairs.

It is often the forceful flexion of your arm at the shoulder required in these activities that overloads the deltoids.

Trauma from the impact of contact sports to being hit by baseball, tennis ball or golf ball, can activate deltoid trigger points.

If you slip on the stairs to the effort of suddenly reaching for the handrail can activate trigger points in your deltoids. Consider gently maintaining contact with the rail as you walk up and down stairs.

Whiplash events can unleash a series of trigger point activations that often includes the deltoids. Some of these trigger points may develop weeks or even months later and can cause debilitating headaches and shoulder pain.

Trigger points in your deltoids can develop from cumulative stress of repeated lifting of your arms. Carrying heavy objects and holding children can also overload the shoulder muscles.

However, simple things improper postures and poor furniture for office and desk workers can have similar impact over time. Studies of mouse and trackpad use suggest that laptop users would benefit from using a mouse to reduce risks for shoulder and upper arm injuries.

Whiplash events can unleash a series of trigger point activations that often includes the deltoids. Some of these trigger points may develop weeks or even months later and can cause debilitating headaches and shoulder pain.

Trigger points in your deltoids can develop from cumulative stress of repeated lifting of your arms. Carrying heavy objects and holding children can also overload the shoulder muscles.

However, simple things improper postures and poor furniture for office and desk workers can have similar impact over time. Studies of mouse and trackpad use suggest that laptop users would benefit from using a mouse to reduce risks for shoulder and upper arm injuries.

The incidence of trigger points is about the same between manual/trade workers and office workers. For instance, holding a power tool up near shoulder height causes a similar overload in the front deltoid to using a mouse. In both cases the eyes and hands are focused on a task tha requires coordination of the musculature of the hand, arm, shoulder, neck, head and face.

The incidence of trigger points is about the same between manual/trade workers and office workers. For instance, holding a power tool up near shoulder height causes a similar overload in the front deltoid to using a mouse. In both cases the eyes and hands are focused on a task tha requires coordination of the musculature of the hand, arm, shoulder, neck, head and face.

Deltoid trigger points are also prevalent in competetive athletes in overhead sports. An overhead tennis or volleyball serve or spike can activate deltoid trigger points.

The posterior deltoid does not usually develop trigger points in isolation. This is more likely to happen as part of a pattern of movement changes. However, certain activities that isolate the posterior deltoid, like rowing or poling when skiing can activate trigger points in the muscle

Deltoid trigger points are also prevalent in competetive athletes in overhead sports. An overhead tennis or volleyball serve or spike can activate deltoid trigger points.

The posterior deltoid does not usually develop trigger points in isolation. This is more likely to happen as part of a pattern of movement changes. However, certain activities that isolate the posterior deltoid, like rowing or poling when skiing can activate trigger points in the muscle

You might consider that a warm up and use smaller ball or a hand knobber tool target more tender areas. Maintain pressure on tender areas for 15-60 seconds. This self-release can be repeated several times a day until the trigger points are inactivated.

You might consider that a warm up and use smaller ball or a hand knobber tool target more tender areas. Maintain pressure on tender areas for 15-60 seconds. This self-release can be repeated several times a day until the trigger points are inactivated.

The Backnobber tool pictured works for most body areas but we also like using the Knobble tool, especially for the front deltoid. Self-release of the shoulder can be more comfortable while seated under a warm shower. These plastic tools work well that too.

The Backnobber tool pictured works for most body areas but we also like using the Knobble tool, especially for the front deltoid. Self-release of the shoulder can be more comfortable while seated under a warm shower. These plastic tools work well that too.

To stretch the posterior deltoid, this common stretch across the chest works well. Try to keep the arm straight and high enough back full contact with your ribs, rather than the the breasts.

To stretch the posterior deltoid, this common stretch across the chest works well. Try to keep the arm straight and high enough back full contact with your ribs, rather than the the breasts.

To stretch the middle deltoid, internally rotate the arm behind your back and gently pull to the opposite side and down. Note that it would be best to place a towel roll (not pictured) between your arm and body for this and many other shoulder stretches and exercises.

To stretch the middle deltoid, internally rotate the arm behind your back and gently pull to the opposite side and down. Note that it would be best to place a towel roll (not pictured) between your arm and body for this and many other shoulder stretches and exercises.

The reason we do this is to avoid unintentionally stretching and activating trigger points the supraspinatus. Because this function of this muscle is so foundational to the function of the deltoids, we want to treat it gently. Note that this practice is commonly depicted in other shoulder and rotator cuff strenghtening photos and videos, but less often for stretches.

Following pressure release or stretching a cold pack may be helpful.

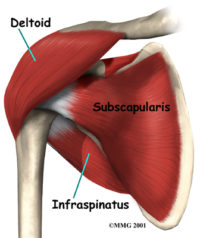

If tightness of the posterior capsule develops it is essential that the connective tissue function with the joint be addressed in addition to restoring normal mechanics of your arm and shoulder while treating trigger points in the infraspinatus.

The reason we do this is to avoid unintentionally stretching and activating trigger points the supraspinatus. Because this function of this muscle is so foundational to the function of the deltoids, we want to treat it gently. Note that this practice is commonly depicted in other shoulder and rotator cuff strenghtening photos and videos, but less often for stretches.

Following pressure release or stretching a cold pack may be helpful.

If tightness of the posterior capsule develops it is essential that the connective tissue function with the joint be addressed in addition to restoring normal mechanics of your arm and shoulder while treating trigger points in the infraspinatus.

For office and desk workers, chronic shoulder pain is associated with trigger points in the various shoulder muscles, including the deltoid. A desk or workstation with poor ergonomics causes prolonged strain on your deltoid and this can be a potent generator of neck and shoulder pain.

For office and desk workers, chronic shoulder pain is associated with trigger points in the various shoulder muscles, including the deltoid. A desk or workstation with poor ergonomics causes prolonged strain on your deltoid and this can be a potent generator of neck and shoulder pain.

Many people doing physical work in various trades have less control over their work environment. If your trade and the project you are working on are punishing to your body, it is even more important to use your body carefully to avoid unusual positions for prolonged periods, improper lifting and carrying and sustained pressure on your shoulders.

Many people doing physical work in various trades have less control over their work environment. If your trade and the project you are working on are punishing to your body, it is even more important to use your body carefully to avoid unusual positions for prolonged periods, improper lifting and carrying and sustained pressure on your shoulders.

A thorough assessment includes proper adjustment of the chair, desk and keyboard so that your elbow is support at about 90 degrees of flexion. This is a routine part of a myofascial assessment and recommedations for corrective actions.

Be careful on stairs to avoid slipping and suddenly reaching for the handrail. Consider gently maintaining contact with the rail as you walk up and down stairs.

Do not practice contact sports without protection for your deltoids. There is a reason football players have huge shoulder pads. If you practice target shooting or hunt regularly, consider a pad for the front of your shoulder.

When you are doing heavy lifting or exercises to strengthen your upper back and shoulders, rotate your arm to that your thumb is turned in the direction that unload most active part of the muscle. So, if you want to assist in unloading your anterior deltoid fibers, you should rotate your thumbs and arms externally. Conversely, internal rotation unloads the posterior deltoid.

A thorough assessment includes proper adjustment of the chair, desk and keyboard so that your elbow is support at about 90 degrees of flexion. This is a routine part of a myofascial assessment and recommedations for corrective actions.

Be careful on stairs to avoid slipping and suddenly reaching for the handrail. Consider gently maintaining contact with the rail as you walk up and down stairs.

Do not practice contact sports without protection for your deltoids. There is a reason football players have huge shoulder pads. If you practice target shooting or hunt regularly, consider a pad for the front of your shoulder.

When you are doing heavy lifting or exercises to strengthen your upper back and shoulders, rotate your arm to that your thumb is turned in the direction that unload most active part of the muscle. So, if you want to assist in unloading your anterior deltoid fibers, you should rotate your thumbs and arms externally. Conversely, internal rotation unloads the posterior deltoid.

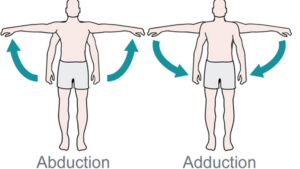

The separate front, middle and rear deltoid muscles can contract at the same time or individually. When all its fibers contract simultaneously, the primary function of the deltoids is to raise (abduct) your arm at your side. They are the strongest and most important muscle for abduction of your arm at your shoulder.

Although the fiber direction of the front and rear deltoids would suggest that they participate in rotation, EMG research has shown that is not true. However, the front deltoid appear to assist in flexion of your arm at your shoulder and the posterior fibers perform extension of your arm behind your back.

The separate front, middle and rear deltoid muscles can contract at the same time or individually. When all its fibers contract simultaneously, the primary function of the deltoids is to raise (abduct) your arm at your side. They are the strongest and most important muscle for abduction of your arm at your shoulder.

Although the fiber direction of the front and rear deltoids would suggest that they participate in rotation, EMG research has shown that is not true. However, the front deltoid appear to assist in flexion of your arm at your shoulder and the posterior fibers perform extension of your arm behind your back.

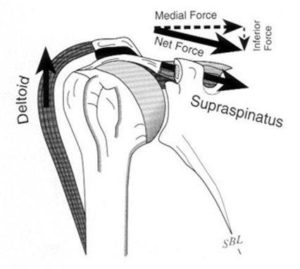

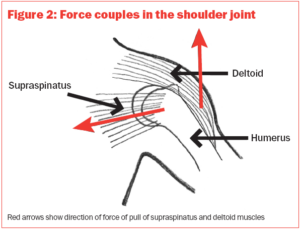

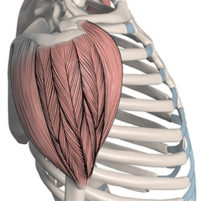

The efficiency of the deltoid muscles depends on the effectiveness of the smaller, underlying rotator cuff muscles, especially the supraspinatus. If this muscle or its tendon are damaged, overloaded, inhibited, weak or firing at the wrong time it will not be able to assist your deltoid in abduction.

We had thought that the deltoid and supraspinatus acted differently on our shoulder joint during arm abduction. However, the activity of both muscles continues and increases throughout movement. But we can see that the nature of that movement changes as your arm raises to 90 degrees and beyond.

The efficiency of the deltoid muscles depends on the effectiveness of the smaller, underlying rotator cuff muscles, especially the supraspinatus. If this muscle or its tendon are damaged, overloaded, inhibited, weak or firing at the wrong time it will not be able to assist your deltoid in abduction.

We had thought that the deltoid and supraspinatus acted differently on our shoulder joint during arm abduction. However, the activity of both muscles continues and increases throughout movement. But we can see that the nature of that movement changes as your arm raises to 90 degrees and beyond.

As you initiate the movement of raising your arm both your deltoid and supraspinatus contract. However, with your arm at your side your deltoid is pulling straight up. Because your supraspinatus attaches to the upper part of the head of your humerus, its connection is tangent to the head and can better initiate the upward movement. At angles below about 45 degrees of abduction the lengths of the lever arms of the two muscles also favor the supraspinatus.

As you initiate the movement of raising your arm both your deltoid and supraspinatus contract. However, with your arm at your side your deltoid is pulling straight up. Because your supraspinatus attaches to the upper part of the head of your humerus, its connection is tangent to the head and can better initiate the upward movement. At angles below about 45 degrees of abduction the lengths of the lever arms of the two muscles also favor the supraspinatus.

As your arm gets above 45 degrees, we can see that what had been an upward movement of the deltoid at the shoulder joint starts to become an upward movement of the arm around the fulcrum of that joint. The higher you raise your arm, the more the work of supraspinatus becomes engaged in pulling the head of the humerus into the joint to help maintain that fulcrum and the stability of your shoulder.

EMG research has also established that the deltoid, along with most of the muscles of the shoulder girdle engage to stabilize against the movement of our arm before we attempt the movement regardless of load.

As your arm gets above 45 degrees, we can see that what had been an upward movement of the deltoid at the shoulder joint starts to become an upward movement of the arm around the fulcrum of that joint. The higher you raise your arm, the more the work of supraspinatus becomes engaged in pulling the head of the humerus into the joint to help maintain that fulcrum and the stability of your shoulder.

EMG research has also established that the deltoid, along with most of the muscles of the shoulder girdle engage to stabilize against the movement of our arm before we attempt the movement regardless of load.

Anterior (Front) Deltoid

The anterior fibers assist the pectoralis major to flex the shoulder. The anterior deltoid also works in tandem with the subscapularis, pecs and lats to internally (medially) rotate the humerus. The activity of these fibers begins before your arm moves to help stabilize the body against the movement. The anterior deltoid also helps flex your arm forward at the shoulder. When your arm is rotated internally the anterior deltoids can also work weakly an adductor. Mechanically, your arm must be medially rotated for the deltoid to have maximum effect in flexion and adduction. This makes the deltoid an antagonist muscle of the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi. In fact, internal rotation to 45 degrees also increases the activity of your anterior deltoid abduction. However, EMG studies have not shown activity of the anterior deltoid in performing internal rotation. Lateral (Middle) Deltoid

Lateral (Middle) Deltoid

The lateral fibers perform basic shoulder abduction when the shoulder is internally rotated (normal position of your arm at your side), and perform shoulder transverse abduction when the shoulder is externally rotated (thumbs out and up). They are not utilized significantly during strict transverse extension (shoulder internally rotated) such as in rowing movements, which use the posterior fibers.

The middle deltoid also assists in flexion of your shoulder, with maximum activity as you approach 90 degrees.

When any of the muscles in the rotator cuff become dysfunctional, the middle deltoid is disadvantaged during abduction.

However, the front deltoid appears to be able to adapt and take over some additional function in abduction and assist the weaked rotator cuff muscles.

Posterior (Rear) Deltoid

The posterior fibers assist the latissimus dorsi to extend your shoulder. Other transverse extensors, the infraspinatus and teres minor, also work in tandem with the posterior deltoid as external (lateral) rotators. These are antagonists to strong internal rotators like the pecs and lats. This ability to extend our arm at the shoulder is a necessary part of many sports. It is also essential for toileting, grooming and dressing activies. Although it appears the posterior deltoid should be able to rotate the able, EMG studies have shown otherwise. Along with the front and middle deltoids, the rear deltoid is active during abduction and elevation of our arm. However, maximum EMG activity of some of the posterior fibers does not occur until the arm is raised to 140 degrees, almost straight up, and this is believed to be a force counter balancing the abduction of the rest of the deltoid fibers.Dynamic Stabilization

During pushing the anterior deltoid is maximally active with help from the middle deltoid. The posterior deltoid is most active when pulling. In throwing the posterior deltoid is active during quick throwing activities, probably to assist deceleration of the shoulder joint. This would suggest that the anterior deltoid is an accelerator in the throwing motion but this has not been widely studied. In freestyle swimming, the front and middle deltoids had the most activity during the early to late recovery phases of the crawl stroke. In swimmers with painful shoulders, it appears that this activity is inhibited. Trigger points can cause this type of inhibition when overloaded. When driving, the raising your hands to the top of wheel activitates the front deltoids with some help from the middle. When the steering wheel is held toward the middle the activity of the muscles is balanced. The rear deltoids where most active when as the torque on the steering wheel increases. An important function of the deltoid in humans is preventing the dislocation of the humeral head when a person carries heavy loads. The function of abduction also means that it would help keep carried objects a safer distance away from the thighs to avoid hitting them, as during a farmer's walk. It also ensures a precise and rapid movement of the shoulder joint needed for hand and arm manipulation. The lateral fibers are in the most efficient position to perform this role, though like basic abduction movements (such as lateral raise) it is assisted by simultaneous co-contraction of anterior/posterior fibers. The deltoid muscle is the muscle forming the rounded contour of the human shoulder. It is also known as the 'common shoulder muscle', particularly in other animals such as the domestic cat. Anatomically, it appears to be made up of three distinct sets of fibers though electromyography suggests that it consists of at least seven groups that can be independently coordinated by the nervous system.

The deltoid muscle is the muscle forming the rounded contour of the human shoulder. It is also known as the 'common shoulder muscle', particularly in other animals such as the domestic cat. Anatomically, it appears to be made up of three distinct sets of fibers though electromyography suggests that it consists of at least seven groups that can be independently coordinated by the nervous system.

It was previously called the deltoideus (plural deltoidei) and the name is still used by some anatomists. It is called so because it is in the shape of the Greek capital letter delta (Δ). Deltoid is also further shortened in slang as "delt".

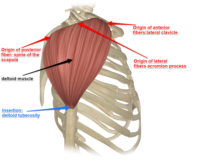

Your deltoids sit like a muscular 'cap' over the rotator cuff muscles. Its length and position of the attachments give it the ability to powerfully raise the arm from your side (abduct).

A study of 30 shoulders revealed an average mass of 191.9 grams (6.77 oz) in humans, ranging from 84 grams (3.0 oz) to 366 grams (12.9 oz).

It was previously called the deltoideus (plural deltoidei) and the name is still used by some anatomists. It is called so because it is in the shape of the Greek capital letter delta (Δ). Deltoid is also further shortened in slang as "delt".

Your deltoids sit like a muscular 'cap' over the rotator cuff muscles. Its length and position of the attachments give it the ability to powerfully raise the arm from your side (abduct).

A study of 30 shoulders revealed an average mass of 191.9 grams (6.77 oz) in humans, ranging from 84 grams (3.0 oz) to 366 grams (12.9 oz).

Structure

Previous studies showed that the insertion of the intramuscular tendons of the deltoid muscle formed three discrete sets of muscle fibers, often referred to as "heads":

Previous studies showed that the insertion of the intramuscular tendons of the deltoid muscle formed three discrete sets of muscle fibers, often referred to as "heads":

- The anterior or clavicular fibers arise from most of the front border and upper surface of the outside third of the clavicle. The origin on the front lies next to the outside fibers of the pectoralis major as do the end tendons of both muscles. These muscle fibers are closely related and only a small space prevents the two muscles from forming a continuous muscle mass. The anterior deltoids are commonly called front delts for short.

- Lateral or acromial fibers arise from the superior surface of the acromion process of the scapula. They are commonly called lateral deltoid. This muscle is also called middle delts, outer delts, or side delts for short.

- Posterior or spinal fibers arise from the lower lip of the posterior border of the spine of the scapula. They are commonly called posterior deltoid or rear deltoid (rear delts for short).

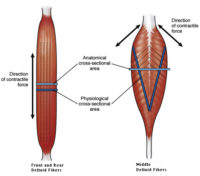

There have been some significant differences between the anatomical divisions of the deltoid that have been visually and functionally observed and the results of EMG studies. Multipennate muscles are much stronger than parallel fiber arrangements. We can see that the middle deltoids are structured for maximum power in abduction. The anterior and posterior parts almost appear to be 'outriggers.'

There have been some significant differences between the anatomical divisions of the deltoid that have been visually and functionally observed and the results of EMG studies. Multipennate muscles are much stronger than parallel fiber arrangements. We can see that the middle deltoids are structured for maximum power in abduction. The anterior and posterior parts almost appear to be 'outriggers.'

Researchers have divided these three groups of fibers, referred to as parts or bands, into seven functional components : the anterior part has two components (I and II); the lateral one (III); and the posterior four (IV, V, VI, and VII) components. In standard anatomical position (with the upper limb hanging alongside the body), the central components (II, III, and IV) lie lateral to the axis of abduction and therefore contribute to abduction from the start of the movement.

However the other components (I, V, VI, and VII) initially act as adductors. During abduction most of these latter components (except VI and VII which always act as adductors) are displaced to the outside and progressively start to abduct.

Researchers have divided these three groups of fibers, referred to as parts or bands, into seven functional components : the anterior part has two components (I and II); the lateral one (III); and the posterior four (IV, V, VI, and VII) components. In standard anatomical position (with the upper limb hanging alongside the body), the central components (II, III, and IV) lie lateral to the axis of abduction and therefore contribute to abduction from the start of the movement.

However the other components (I, V, VI, and VII) initially act as adductors. During abduction most of these latter components (except VI and VII which always act as adductors) are displaced to the outside and progressively start to abduct.