The subscapularis muscle is the largest of the four rotator cuff muscles. It is responsible for internal rotation and adduction of the your arm at the shoulder. Most importantly, in conjunction with the other rotator cuff muscles, it is responsible for dynamic stabilization of the shoulder joint. The shoulder has less connective tissue structure than other major joints. The rotator cuff muscles act as a sort of dynamic muscle/ligament hybrid to stabilize the shoulder joint as you move. Of the important function of subscapularis is to provide dynamic restraint to the back side of the shoulder joint.

The subscapularis muscle is the largest of the four rotator cuff muscles. It is responsible for internal rotation and adduction of the your arm at the shoulder. Most importantly, in conjunction with the other rotator cuff muscles, it is responsible for dynamic stabilization of the shoulder joint. The shoulder has less connective tissue structure than other major joints. The rotator cuff muscles act as a sort of dynamic muscle/ligament hybrid to stabilize the shoulder joint as you move. Of the important function of subscapularis is to provide dynamic restraint to the back side of the shoulder joint.

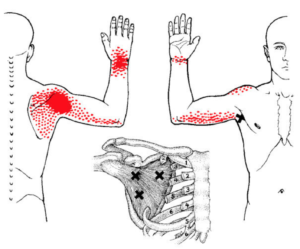

Trigger points in your subscapularis cause pain in the back of the shoulder, and sometimes extending down the back of your arm. Referred pain can also develop on the back side of your hand, wrist, forearm.

Subscapularis trigger points are often involved with Frozen Shoulder Syndrome. They are frequently the foundation of an entire range of shoulder dysfunction.

Trigger points can be activated anywhere in the subscapularis from unaccustomed eccentric loading, eccentric exercise in an unconditioned muscle, maximal or sub-maximal concentric loading.

Placing the muscle in a shortened or lengthened position for an extended period of time can also activate trigger points in the subscapularis. This happens most often when we are sleeping or driving.

Trigger points can be activated anywhere in the subscapularis from unaccustomed eccentric loading, eccentric exercise in an unconditioned muscle, maximal or sub-maximal concentric loading.

Placing the muscle in a shortened or lengthened position for an extended period of time can also activate trigger points in the subscapularis. This happens most often when we are sleeping or driving.

Activies that can overload your subscapularis include repeated forceful internal rotation. Examples include throwing a baseball, a tennis serve or freestyle swimming. Other activities that can activate subscapularis are involve repeated overhead lifting, such as poorly performed kettle bell swings.

Less dramatic movements can also cause activations, such as the sudden overload from reaching to grab a railing on a stairway when you lose balance.

Activies that can overload your subscapularis include repeated forceful internal rotation. Examples include throwing a baseball, a tennis serve or freestyle swimming. Other activities that can activate subscapularis are involve repeated overhead lifting, such as poorly performed kettle bell swings.

Less dramatic movements can also cause activations, such as the sudden overload from reaching to grab a railing on a stairway when you lose balance.

Local trauma such as dislocation, joint capsule tears, fractures, or prolonged immobilization of the shoulder in an adducted, internally rotated position can activate and perpetuate trigger points in the related muscles such as subscapularis. Other procedures such as mastectomy, lumpectomy, or radiation treatment can also do this.

Once these trigger points have been established they can be perpetuated by slumped posture or other repeated movements that internally rotate your arm.

Local trauma such as dislocation, joint capsule tears, fractures, or prolonged immobilization of the shoulder in an adducted, internally rotated position can activate and perpetuate trigger points in the related muscles such as subscapularis. Other procedures such as mastectomy, lumpectomy, or radiation treatment can also do this.

Once these trigger points have been established they can be perpetuated by slumped posture or other repeated movements that internally rotate your arm.

Myofascial self care always starts with establishing a foundation of diaphragmatic breathing. Once you have taken a few moments get in touch with your breath, we move on to self-compression.

Recall that the subscapularis muscle is on the INSIDE of your shoulder blade. This nice lady with the big foam roller might be doing some good, but there is no chance she is going to get underneath her scapula to find that muscle.

Myofascial self care always starts with establishing a foundation of diaphragmatic breathing. Once you have taken a few moments get in touch with your breath, we move on to self-compression.

Recall that the subscapularis muscle is on the INSIDE of your shoulder blade. This nice lady with the big foam roller might be doing some good, but there is no chance she is going to get underneath her scapula to find that muscle.

In fact, as you can see from relative size of the shoulder blade and the tennis ball, that is will be hard to get any type of roller or ball in there.

In fact, as you can see from relative size of the shoulder blade and the tennis ball, that is will be hard to get any type of roller or ball in there.

However, if you position yourself carefully, on your side, with your arm extended, you might be able to access a small part of subscapularis in this way.

In most cases, you will have better luck with a knobber of some type that has a smaller head. We like the Back Knobber from Pressure Positive.

However, if you position yourself carefully, on your side, with your arm extended, you might be able to access a small part of subscapularis in this way.

In most cases, you will have better luck with a knobber of some type that has a smaller head. We like the Back Knobber from Pressure Positive.

This type of tool allows you get into the armpit and into the space behind the shoulder blade. Approach this slowly and gently. If it is too painful you are pushing too hard, or too fast. You may need to experiment with your tool and a body position that faciliates accessing subscapularis.

There are a lot of blood vessels and nerves in the armpit, so any self- release should be done with caution. If you feel tingling or circulation changes in your arm you should reposition and take a different approach.

This type of tool allows you get into the armpit and into the space behind the shoulder blade. Approach this slowly and gently. If it is too painful you are pushing too hard, or too fast. You may need to experiment with your tool and a body position that faciliates accessing subscapularis.

There are a lot of blood vessels and nerves in the armpit, so any self- release should be done with caution. If you feel tingling or circulation changes in your arm you should reposition and take a different approach.

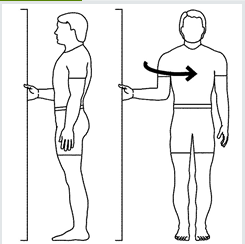

You can also learn to release tightness in the subscapularis by slowly and firmly stretching it using the the middle hand positions in the doorway. It is a little like a doorway stretch to open your chest. However, in this stretch, you are externally rotating your upper arm and stretching the subscapularis.

A firm, but gentle and pain-free stretch can be held for 30 seconds and repeated three to five times. You can augment this stretch with a PNF hold-relax technique.

Gently push into the door frame with internal rotation to minimally contract the subscapularis muscle for five to ten seconds, followed by relaxation. Then gently stretch the muscle into external rotation by rotating the body away from the doorframe.

Another approach is to use your breath to deepen the stretch. As you inhale, gently push into the doorframe. As you exhale, gently stretch by rotating the body away from the doorframe. You can repeat this sequence three to five times, up to four times per day.

Following pressure release or stretching a cold pack may be helpful.

If tightness of the posterior capsule develops it is essential that the connective tissue function with the joint be addressed in addition to restoring normal mechanics of your arm and shoulder while treating trigger points in the subscapularis. If treatment is limited to this individual muscle without addressing the mechanics of the entire joint will fail and pain relief will be temporary.

You can also learn to release tightness in the subscapularis by slowly and firmly stretching it using the the middle hand positions in the doorway. It is a little like a doorway stretch to open your chest. However, in this stretch, you are externally rotating your upper arm and stretching the subscapularis.

A firm, but gentle and pain-free stretch can be held for 30 seconds and repeated three to five times. You can augment this stretch with a PNF hold-relax technique.

Gently push into the door frame with internal rotation to minimally contract the subscapularis muscle for five to ten seconds, followed by relaxation. Then gently stretch the muscle into external rotation by rotating the body away from the doorframe.

Another approach is to use your breath to deepen the stretch. As you inhale, gently push into the doorframe. As you exhale, gently stretch by rotating the body away from the doorframe. You can repeat this sequence three to five times, up to four times per day.

Following pressure release or stretching a cold pack may be helpful.

If tightness of the posterior capsule develops it is essential that the connective tissue function with the joint be addressed in addition to restoring normal mechanics of your arm and shoulder while treating trigger points in the subscapularis. If treatment is limited to this individual muscle without addressing the mechanics of the entire joint will fail and pain relief will be temporary.

Shoulder pain and limited range of motion are the hallmarks of subscapularis trigger points. Pain is usually concentrated near the back of the shoulder. In addition, pain and tightness often travel down the arm, skipping the elbow and causing pain on the top side of the wrist and forearm. This is analagous to the gluteus minimus referrals that skip the knee and pop up again in the calf.

Rotator cuff issues are at least one of the factors in many cases of shoulder pain. The subscapularis muscle is one of the most likely muscles to have developed TrPs. For instance, in individuals diagnosed with shoulder impingement syndrome 42% had active trigger points in their subscapularis muscle.

Shoulder pain and limited range of motion are the hallmarks of subscapularis trigger points. Pain is usually concentrated near the back of the shoulder. In addition, pain and tightness often travel down the arm, skipping the elbow and causing pain on the top side of the wrist and forearm. This is analagous to the gluteus minimus referrals that skip the knee and pop up again in the calf.

Rotator cuff issues are at least one of the factors in many cases of shoulder pain. The subscapularis muscle is one of the most likely muscles to have developed TrPs. For instance, in individuals diagnosed with shoulder impingement syndrome 42% had active trigger points in their subscapularis muscle.

In the early stages of myofascial dysfunction of subscapularis, you may experience decreased ability to raise and externally rotate your arm, as if to throw a ball, or to rotate and reach back from the front seat of a car. Typically, this progresses to the point where your arm can only be lifted to a 45% angle or less.

In addition, you may have pain at rest, pain with movement and the inability to reach the opposite shoulder or armpit (as you might when applying deodorant). Because of the severe pain and limitations in range of motion, you could be diagnosed with 'adhesive capsulitis' or 'frozen shoulder.' These are vague and insufficient diagnoses that do not get to the root of the problem.

Pain in top of the hand, wrist and forearm, as well as a feeling of 'tightness', can be significant, especially when reaching overhead. If it is the same side that you wear your watch, fitbit, etc, you may feel like moving it the other wrist.

Popping or clicking sounds near the shoulder may be due to subscapularis or supraspinatus trigger points.

In the early stages of myofascial dysfunction of subscapularis, you may experience decreased ability to raise and externally rotate your arm, as if to throw a ball, or to rotate and reach back from the front seat of a car. Typically, this progresses to the point where your arm can only be lifted to a 45% angle or less.

In addition, you may have pain at rest, pain with movement and the inability to reach the opposite shoulder or armpit (as you might when applying deodorant). Because of the severe pain and limitations in range of motion, you could be diagnosed with 'adhesive capsulitis' or 'frozen shoulder.' These are vague and insufficient diagnoses that do not get to the root of the problem.

Pain in top of the hand, wrist and forearm, as well as a feeling of 'tightness', can be significant, especially when reaching overhead. If it is the same side that you wear your watch, fitbit, etc, you may feel like moving it the other wrist.

Popping or clicking sounds near the shoulder may be due to subscapularis or supraspinatus trigger points.

Avoid repetitive actions that overload the muscle, such as throwing, golfing, etc. However you should also avoid lifting heavy objects from the floor or from a high shelf. This requires major dynamic stabilization of the shoulder and also strongly engages your bicep. Because the subscapularis and bicep have an intimate connection, this can be problematic.

Be careful to avoid forward head posture and rounding of your shoulders. These postures are typical of desk work, computer work, texting and driving. Getting up to move frequently can help avoid keeping your arm too close to your side for long periods.

If you are driving long distances, use the arm rest, if available. If not, a small bolster or towel roll between you arm and body will allow your arm to rest more naturally.

Avoid repetitive actions that overload the muscle, such as throwing, golfing, etc. However you should also avoid lifting heavy objects from the floor or from a high shelf. This requires major dynamic stabilization of the shoulder and also strongly engages your bicep. Because the subscapularis and bicep have an intimate connection, this can be problematic.

Be careful to avoid forward head posture and rounding of your shoulders. These postures are typical of desk work, computer work, texting and driving. Getting up to move frequently can help avoid keeping your arm too close to your side for long periods.

If you are driving long distances, use the arm rest, if available. If not, a small bolster or towel roll between you arm and body will allow your arm to rest more naturally.

Restful sleep may be difficult due to pain. Consider sleeping on your back or on the uninvolved side. If you sleep on the pain-free side your sleep will be improved if you support the painful arm on a pillow, avoiding the prolonged shortening that can lead to pain.

Restful sleep may be difficult due to pain. Consider sleeping on your back or on the uninvolved side. If you sleep on the pain-free side your sleep will be improved if you support the painful arm on a pillow, avoiding the prolonged shortening that can lead to pain.

You can also use this technique to support the painful arm when sleeping on your back or when sitting.

In general, do not sleep on your stomach. Do not lie on either on your back with your arms extended up over your head. This will externally rotate your arms and keep the subscapularis in a lengthened position for an extended time.

You can also use this technique to support the painful arm when sleeping on your back or when sitting.

In general, do not sleep on your stomach. Do not lie on either on your back with your arms extended up over your head. This will externally rotate your arms and keep the subscapularis in a lengthened position for an extended time.

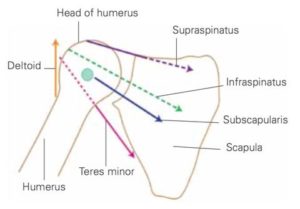

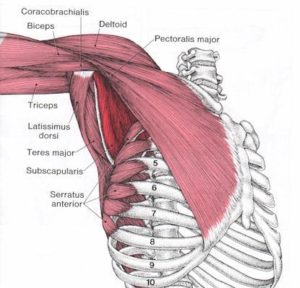

Although these rotator cuff muscles participate in rotation of your arm, their primary purpose is to pull the head of humerus fairly tight into the shallow socket of the shoulder blade. Unlike your knee or ankle, this stability is created by largely these rotator cuff muscles, not ligaments. It part of what allows us to have much greater range of motion at our shoulder than any other joint. For this stabilizing function, you could think of them as powered, dynamic ligaments.

Of the rotator cuff muscles, subscapularis is the most dominant stabilizer of the shoulder joint. When viewed from the top, we would see that the subscapularis crosses from the back of the shoulder blade to the front of the humerus. This stabilizes the joint against anterior dislocation as well, especially if the arm is raised.

Although these rotator cuff muscles participate in rotation of your arm, their primary purpose is to pull the head of humerus fairly tight into the shallow socket of the shoulder blade. Unlike your knee or ankle, this stability is created by largely these rotator cuff muscles, not ligaments. It part of what allows us to have much greater range of motion at our shoulder than any other joint. For this stabilizing function, you could think of them as powered, dynamic ligaments.

Of the rotator cuff muscles, subscapularis is the most dominant stabilizer of the shoulder joint. When viewed from the top, we would see that the subscapularis crosses from the back of the shoulder blade to the front of the humerus. This stabilizes the joint against anterior dislocation as well, especially if the arm is raised.

As the largest and strongest of the rotator cuff muscles, subscapularis is also a powerful internal rotator of your arm. However, movement at the shoulder joint is a complex, coordinated activity.

For instance, when your middle deltoid elevates your shoulder, the head of your humerus wants rise up out of the socket. The lever arms of the the rotator cuff generally exert their force down and in towards the joint. In conjunction with your infraspinatus, subscapularis resists this upward force and keeps the humerus down in the socket. In fact, some studies have shown that ALL the rotator cuff muscles activate just before the arm raises in abduction.

As the largest and strongest of the rotator cuff muscles, subscapularis is also a powerful internal rotator of your arm. However, movement at the shoulder joint is a complex, coordinated activity.

For instance, when your middle deltoid elevates your shoulder, the head of your humerus wants rise up out of the socket. The lever arms of the the rotator cuff generally exert their force down and in towards the joint. In conjunction with your infraspinatus, subscapularis resists this upward force and keeps the humerus down in the socket. In fact, some studies have shown that ALL the rotator cuff muscles activate just before the arm raises in abduction.

Finally, subscapularis is considered an adductor of the shoulder and pulls your arm down towards your body from the side. Because of the different angles of muscle fibers in the upper and lower compartments, we can explain conflicting research suggesting that subscapularis is both a weak abductor and as well as an adductor of the shoulder.

Unlike other rotator cuff muscles, during a throwing motion, subscapularis is most active during the acceleration phase of the movement. The other rotator cuff muscles activate to decelerate the arm when throwing.

Finally, subscapularis is considered an adductor of the shoulder and pulls your arm down towards your body from the side. Because of the different angles of muscle fibers in the upper and lower compartments, we can explain conflicting research suggesting that subscapularis is both a weak abductor and as well as an adductor of the shoulder.

Unlike other rotator cuff muscles, during a throwing motion, subscapularis is most active during the acceleration phase of the movement. The other rotator cuff muscles activate to decelerate the arm when throwing.

During a tennis serve, subscapularis is most active during late cocking and early acceleration. During a golf swing, activity tends to increase through acceleration of your dominant shoulder and maintain some activity throughout the swing of the your non-dominant shoulder.

In healthy freestyle swimmers, subscapularis is active throughout their stroke. However, swimmers with painful shoulders show about a 50% drop in activation of this same muscle during the recovery phase of their stroke.

During a tennis serve, subscapularis is most active during late cocking and early acceleration. During a golf swing, activity tends to increase through acceleration of your dominant shoulder and maintain some activity throughout the swing of the your non-dominant shoulder.

In healthy freestyle swimmers, subscapularis is active throughout their stroke. However, swimmers with painful shoulders show about a 50% drop in activation of this same muscle during the recovery phase of their stroke.

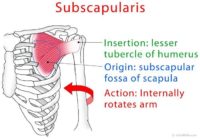

The subscapularis muscle is the largest of the four rotator cuff muscles.

It has two heads creating a large, thick triangular mass that fills the subscapular fossa. This fossa is a depression on the inside of your shoulder blade (scapula) - between it and the back of your rib cage.

Subscapularis runs across the entire inside of the scapula and its fibers converge into a central tendon that covers the front of the shoulder joint and inserts into shoulder joint capsule and the humerus.

The subscapularis muscle is the largest of the four rotator cuff muscles.

It has two heads creating a large, thick triangular mass that fills the subscapular fossa. This fossa is a depression on the inside of your shoulder blade (scapula) - between it and the back of your rib cage.

Subscapularis runs across the entire inside of the scapula and its fibers converge into a central tendon that covers the front of the shoulder joint and inserts into shoulder joint capsule and the humerus.

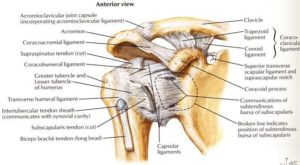

Structure

Coming from the direction of the spine, subscapularis arises from the inner two-thirds and from the lower two-thirds of the groove on the inside of your shoulder blade. Some fibers develop from tendinous layers, which intersect the muscle and are attached to ridges on the bone; others from fibrous sheaths that separate the muscle from the teres major and the long head of the triceps brachii. This firmly anchors the subscapularis to the shoulder blade and the surrounding tissue. The upper fibers mostly run horizontally and merge with the more vertical lower fibers. They coalesce into a tendon that is inserted into the lesser tubercle of the humerus and the anterior part of the shoulder-joint capsule. The thick lower head of the joint capsule provides a majority of the support for the subscapularis tendon. Tendinous fibers also extend to the greater tubercle with insertions into the bicipital groove as detailed below.Relations

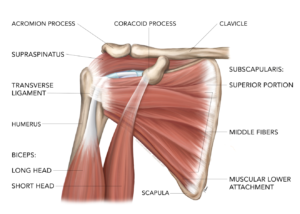

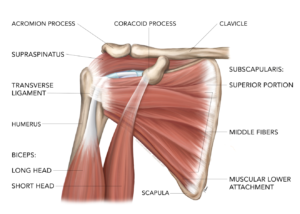

The subscapularis tendon itself has three distinct sections, a thick upper tubular tendon, a flat middle tendon and a muscular lower section. The cross sectional area of this tendon is the largest of all tendons in the shoulder. It dynamically reinforces the ligaments of the shoulder and front labrum. When someone refers to a 'rotator cuff tear' of the subscapalaris muscle they are referring to a tear of this tendon.

This transitional portion of the muscle as it becomes a tendon passes to the outside of the shoulder, beneath the coracoid to insert onto the upper humerus. The insertion of the subscapularis is complex, and recent research into the insertion of the subscapularis tendon describes three distinct sections that are inserted differently:

The subscapularis tendon itself has three distinct sections, a thick upper tubular tendon, a flat middle tendon and a muscular lower section. The cross sectional area of this tendon is the largest of all tendons in the shoulder. It dynamically reinforces the ligaments of the shoulder and front labrum. When someone refers to a 'rotator cuff tear' of the subscapalaris muscle they are referring to a tear of this tendon.

This transitional portion of the muscle as it becomes a tendon passes to the outside of the shoulder, beneath the coracoid to insert onto the upper humerus. The insertion of the subscapularis is complex, and recent research into the insertion of the subscapularis tendon describes three distinct sections that are inserted differently:

- The upper portion blends with the ‘biceps pulley system’ inserting into the greater tuberosity.

- The thick, flat middle portion inserts into the lesser tuberosity.

- The muscular lower attachment inserts directly into the humerus.

Anatomically, the upper portion of subscapularis acts like the supraspinatus muscle and can abduct the arm. The upper fibers of its tendon extend out and up to form part of the biceps tendon groove and merge with the supraspinatus tendon. Fibers from the subscapularis and supraspinatus interlock and converge together as they course around and above the humeral head to their insertion sites on the greater tubercle.

Finally, some subscapularis tendon fibers are contained within a fibrous expansion of the pectoralis major tendon and form the transverse ligament. This is a fascial covering of the vertical portion of the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT), creating a biceps 'sling.' This is connective tissue complex acts to stabilise the LHBT in the bicipital groove. The pulley complex is composed of the superior glenohumeral ligament, the coracohumeral ligament, and the far attachment of the subscapularis tendon.

Anatomically, the upper portion of subscapularis acts like the supraspinatus muscle and can abduct the arm. The upper fibers of its tendon extend out and up to form part of the biceps tendon groove and merge with the supraspinatus tendon. Fibers from the subscapularis and supraspinatus interlock and converge together as they course around and above the humeral head to their insertion sites on the greater tubercle.

Finally, some subscapularis tendon fibers are contained within a fibrous expansion of the pectoralis major tendon and form the transverse ligament. This is a fascial covering of the vertical portion of the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT), creating a biceps 'sling.' This is connective tissue complex acts to stabilise the LHBT in the bicipital groove. The pulley complex is composed of the superior glenohumeral ligament, the coracohumeral ligament, and the far attachment of the subscapularis tendon.

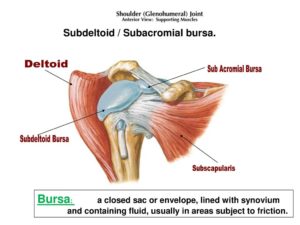

The tendon of the subscapularis is separated from the neck of the scapula by a large bursa, which communicates with the cavity of the shoulder-joint through an aperture in the capsule. This is important because inflammation of the subdeltoid/subacromial bursae (bursitis) can be induced by trigger points in the subscapularis or supraspinatus. The subscapularis is also separated from the serratus anterior by the subscapularis (supraserratus) bursa.

The tendon of the subscapularis is separated from the neck of the scapula by a large bursa, which communicates with the cavity of the shoulder-joint through an aperture in the capsule. This is important because inflammation of the subdeltoid/subacromial bursae (bursitis) can be induced by trigger points in the subscapularis or supraspinatus. The subscapularis is also separated from the serratus anterior by the subscapularis (supraserratus) bursa.

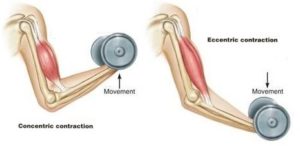

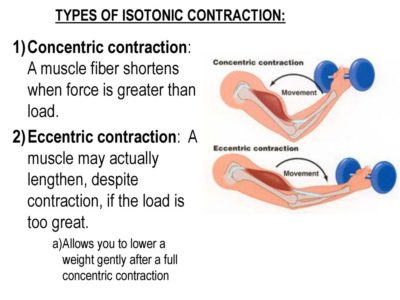

For example, in a biceps curl, you would use a concentric contraction of your biceps, coupled with an eccentric contraction of your triceps, to flex your elbow and push the weight up. As you lower the weight, eccentric contractions of your biceps are required to maintain control and prevent dropping the weight.

For example, in a biceps curl, you would use a concentric contraction of your biceps, coupled with an eccentric contraction of your triceps, to flex your elbow and push the weight up. As you lower the weight, eccentric contractions of your biceps are required to maintain control and prevent dropping the weight.

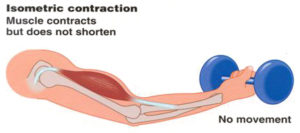

Isotonic Contractions

Isotonic contractions maintain constant tension in the muscle as the muscle changes length. This can occur only when a muscle’s maximal force of contraction exceeds the total load on the muscle. Isotonic muscle contractions can be either concentric (muscle shortens) or eccentric (muscle lengthens).Concentric Contractions

A concentric contraction is a type of muscle contraction in which the muscle shortens while generating force. This is typical of muscles that contract due to the sliding filament mechanism, and it occurs throughout the muscle. Such contractions also alter the angle of the joints to which the muscles are attached. This occurs throughout the length of the muscle, generating force; causing the muscle to shorten and the angle of the joint to change. For instance, a concentric contraction of the biceps would cause the arm to bend at the elbow as the hand moves close to the shoulder (a biceps curl).

A concentric contraction of the triceps would change the angle of the joint in the opposite direction, straightening the arm and moving the hand away from the shoulder.

This occurs throughout the length of the muscle, generating force; causing the muscle to shorten and the angle of the joint to change. For instance, a concentric contraction of the biceps would cause the arm to bend at the elbow as the hand moves close to the shoulder (a biceps curl).

A concentric contraction of the triceps would change the angle of the joint in the opposite direction, straightening the arm and moving the hand away from the shoulder.

Eccentric Contractions

An eccentric contraction results in the lengthening of a muscle. These contractions decelerate muscles and joints (acting as “brakes” to concentric contractions) and can alter the position of the load force. During an eccentric contraction, the muscle lengthens while under tension due to an opposing force that is greater than the force generated by the muscle. However, rather than working to pull a joint in the direction of the muscle contraction, the muscle acts to decelerate the joint at the end of a movement or otherwise control the repositioning of a load. This can occur involuntarily (when attempting to move a weight too heavy for the muscle to lift) or voluntarily (when the muscle is “smoothing out” a movement). Strength training involving both eccentric and concentric contractions appears to increase muscular strength and joint stability more than training with concentric contractions alone.Isometric Contractions

In contrast to isotonic contractions, isometric contractions generate force without changing the length of the muscle. This is typical of muscles found in the hands and forearm: the muscles do not change length, and joints are not moved, so force for grip is sufficient. An example is when the muscles of the hand and forearm grip an object; the joints of the hand do not move, but muscles generate sufficient force to prevent the object from being dropped.

For people with hypermobile joints, strength training can be a challenge. Tension stresses the connective tissues of the joint as force is transmitted through its range of motion. Isometric exercises can be ideal in these circumstances because there is minimal movement. This means that the joint is placed into vulnerable hyperextended positions under force.

In contrast to isotonic contractions, isometric contractions generate force without changing the length of the muscle. This is typical of muscles found in the hands and forearm: the muscles do not change length, and joints are not moved, so force for grip is sufficient. An example is when the muscles of the hand and forearm grip an object; the joints of the hand do not move, but muscles generate sufficient force to prevent the object from being dropped.

For people with hypermobile joints, strength training can be a challenge. Tension stresses the connective tissues of the joint as force is transmitted through its range of motion. Isometric exercises can be ideal in these circumstances because there is minimal movement. This means that the joint is placed into vulnerable hyperextended positions under force. You can develop amazing strength without free weights, machines, or resistance bands.

One of the original bodybuilder gurus from the 1920s, Charles Atlas, based his workouts primarily on isometric exercises, eventually even trademarking a term for his exercise method that he called "Dynamic Tension."

If you have hypermobile joints you can strength train safely at home with isometric exercises.

You can develop amazing strength without free weights, machines, or resistance bands.

One of the original bodybuilder gurus from the 1920s, Charles Atlas, based his workouts primarily on isometric exercises, eventually even trademarking a term for his exercise method that he called "Dynamic Tension."

If you have hypermobile joints you can strength train safely at home with isometric exercises.