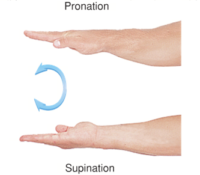

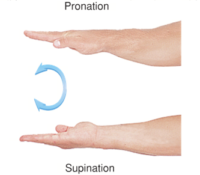

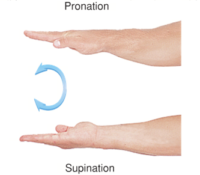

The supinator runs between the bones the radius and ulna in the forearm. It supinates your forearm, turning it palm up. The opposite of this pattern is pronation, rotating the forearm so that your palm faces downward. The causes, pain patterns, corrective actions, and self-care are similar to brachioradialis. Supinator dysfunction is at the root of most cases of lateral epicondylitis, sometimes called “tennis elbow”.

The supinator runs between the bones the radius and ulna in the forearm. It supinates your forearm, turning it palm up. The opposite of this pattern is pronation, rotating the forearm so that your palm faces downward. The causes, pain patterns, corrective actions, and self-care are similar to brachioradialis. Supinator dysfunction is at the root of most cases of lateral epicondylitis, sometimes called “tennis elbow”.

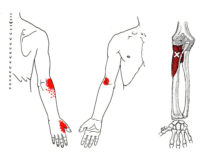

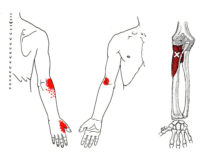

Pain from supinator trigger points often originates on the outside of the forearm, near the elbow. It may also progress down the arm toward the base and web of the thumb.

The primary cause of supinator trigger points is stress overload. This can happen with any activity that involves repeated rotation of your forearm, flexing the wrist, deviating the wrist toward the pinky side, or loading the forearms incorrectly when carrying boxes or packages. The classic example is playing tennis, mis-hitting the ball, off-center, with the arm fully extended, twisting the forearm, and requiring a strong effort to keep the racquet straight.

Less frequent forceful pronation of your wrist (the opposite of supination) can also activate supinator trigger points. For instance, carrying a backpack to work and flipping it onto the desk, palm side down and arm extended, is forceful pronation of your forearm.

When your elbow is flexed, the biceps is the most powerful supinator of the forearm, the supinator merely assists, and injuries are less frequent. When your arm is extended, the much stronger biceps is unable to assist and your supinator becomes the prime mover.

Supinator trigger points do not usually happen in isolation and are part of a pattern that often includes the brachioradialis, brachialis, triceps, wrist, and finger extensors.

Corrective actions include trigger point pressure release, stretching, and avoiding activities that overload the muscle.

Pain at the outside of the elbow, extending up through the forearm to the base of the thumb, is typical of supinator trigger points. The pattern is very similar to brachioradialis trigger points and the two muscles often development dysfunction in concert and should be treated together.

Pain at the outside of the elbow, extending up through the forearm to the base of the thumb, is typical of supinator trigger points. The pattern is very similar to brachioradialis trigger points and the two muscles often development dysfunction in concert and should be treated together.

Pain may concentrate on either the base and web of the thumb and or forearm near the elbow.

Supinator trigger points do not happen in isolation and are part of a pattern that includes the wrist/finger extensors, brachioradialis, brachialis, triceps, and biceps. You may experience weakness in handgrip from other finger extensors but it is typically not caused directly by inhibition of the supinator.

Avoid carrying packages with your palms up, especially with your arms extended. Even better, rotate your arms to a neutral position, with your palms facing each other.

Avoid carrying packages with your palms up, especially with your arms extended. Even better, rotate your arms to a neutral position, with your palms facing each other.  A box or tote with handles can facilitate this but be sure to flex your arms and bring the load closer to your body to allow your supinator and biceps to work together. or pronated (palms down).

A box or tote with handles can facilitate this but be sure to flex your arms and bring the load closer to your body to allow your supinator and biceps to work together. or pronated (palms down).

The best option is to use a hand truck that will allow you to maintain a pronated arm position (hand down) or any other position you desire.

The best option is to use a hand truck that will allow you to maintain a pronated arm position (hand down) or any other position you desire.

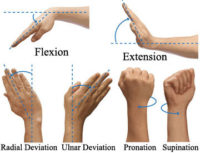

Limit any activity that involves repeated rotation of your forearm, flexing the wrist, deviating the wrist toward the pinky side, or loading the forearms incorrectly when carrying boxes or packages.

The classic example is playing tennis, mis-hitting the ball with one arm, off-center, with the arm fully extended, twisting the forearm, and requiring a strong and unexpected effort to keep the racquet straight. Note that tennis elbow often implies “golfer’s elbow”, an inflammation of the medial (inner) epicondyle, and vice versa. Both golfers and tennis players are vulnerable to similar dysfunction in the forearm.

Less frequent forceful pronation of your wrist (the opposite of supination) can also activate supinator trigger points. For instance, carrying a backpack to work and flipping it onto the desk, palm side down and arm extended, is forceful pronation of your forearm. In this case, the pronation is less important than the sudden stop, which your supinator reacts to forcefully.

Household activities like wringing out a rag or raking leaves require rotation of your forearm or holding the forearm in a pronated position. Try to switch from the right to left side frequently in these activities.

Limit flexion and ulnar deviation of the wrist. Limit forceful rotation of the arm and rapid flexion/extension of the elbow.

A wrist splint similar to ones sold for carpal tunnel syndrome will limit the flexion and ulnar deviation at the wrist and may be helpful for other muscles of the forearm.  An elbow brace that supports the supinator below the elbow and restricts full elbow extension will support the supinator.

An elbow brace that supports the supinator below the elbow and restricts full elbow extension will support the supinator.

Myofascial self-care always starts with establishing a foundation of diaphragmatic breathing. Once you have taken a few moments to get in touch with your breath, we move on to self-compression and stretching. You may find that a warm bath or shower, or applying moist heat before you begin is helpful.

Myofascial self-care always starts with establishing a foundation of diaphragmatic breathing. Once you have taken a few moments to get in touch with your breath, we move on to self-compression and stretching. You may find that a warm bath or shower, or applying moist heat before you begin is helpful.

You can use pressure self-release for the supinator while seated.

You can use pressure self-release for the supinator while seated.

Using your hand from the unaffected side, begin by using your fist to gently massage the top of the forearm just below above the elbow. Note that it runs diagonally from inside to out – the opposite of the closely related brachioradialis.

Explore the muscle, noting areas that are sorer, and bring your focus to them. You can also use your elbow for sustained pressure without stressing your fingers. To compress specific trigger points, use the elbow of the forefinger from the unaffected side to probe deeper.

The most pinpoint pressure and accuracy comes from using the knuckle of your index finger. Make a loose fist with the remaining fingers, extend the knuckle of your index finger and support it with your thumb. Find the tender spot and apply pressure for up to 30 seconds as pain decreases. You can do this three to five times.

Many blood vessels and nerves in the arm are superficial, so pressure self-release should be done with caution. If you feel tingling or circulation changes in your hand you should reposition and take a different approach.

After completing self-compressions, move your arm, hands, and fingers through their range of motion and prepare to gently stretch your supinator. Perform a few wrist circles, extend your fingers and gently shake your hands.

After completing self-compressions, move your arm, hands, and fingers through their range of motion and prepare to gently stretch your supinator. Perform a few wrist circles, extend your fingers and gently shake your hands.

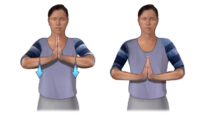

The prayer stretch and reverse prayer stretch primarily extend your wrist and finger flexors.

The prayer stretch and reverse prayer stretch primarily extend your wrist and finger flexors.  However, if you try it you’ll find that these moves also pronate and supinate your forearm.

However, if you try it you’ll find that these moves also pronate and supinate your forearm.

Continue with a supinator stretch, using the opposite hand to gently oppose supination in the arm you are working.

Continue with a supinator stretch, using the opposite hand to gently oppose supination in the arm you are working.

You can finish with this arm-twist. In position 3, you can rotate to each side to deepen the supinator stretch on each side. Note that trigger points in the arms usually occur in grouped patterns. You will probably have a comprehensive routine that includes movements in each functional direction.

You can finish with this arm-twist. In position 3, you can rotate to each side to deepen the supinator stretch on each side. Note that trigger points in the arms usually occur in grouped patterns. You will probably have a comprehensive routine that includes movements in each functional direction.

You can use your breath to deepen the stretches. Begin with a generous inhale and as you exhale, gently stretch to your soft limit, exhale and take another breath. If you experience pain following pressure release and stretching, a cold pack may be helpful.

The video below demonstrates several techniques for strengthening the supinator and pronator:

If you maintain a posture or activity that activates a trigger point in any muscle it will continue.

If you maintain a posture or activity that activates a trigger point in any muscle it will continue.

The primary cause of supinator trigger points is stress overload. This can happen with any activity that involves repetitive, forceful, or unexpected rotation of the forearm. Flexing the wrist, deviating the wrist toward the pinky side, or loading the forearms incorrectly when carrying boxes or packages increases the load on the supinator and related muscles.

Supinator, like the other hand extensors, is more vulnerable when your wrist is flexed or deviated to the little finger side. For example, a heavy tennis racquet or a poor grip on a baseball bat can contribute to trigger point activations.

The classic example of the convergence of these risk factors is playing tennis, mis-hitting the ball off-center, with the arm fully extended, and twisting the forearm. This requires a strong, sudden and unexpected effort to keep the racquet straight.

Less frequent forceful pronation of your wrist (the opposite of supination) can also activate supinator trigger points. For instance, carrying a backpack to work and flipping it onto the desk, palm side down and arm extended, is forceful pronation of your forearm. Gardening also involves significant rotation of the forearm.

With “tennis elbow”, supinator activations are present in virtually every case, regardless of other factors.

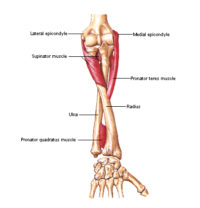

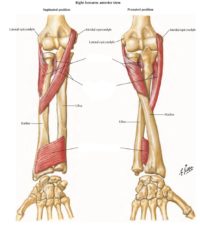

The supinator rotates the forearm (around the ulna) at the elbow.

Encircling the radius, supinator brings the hand into the palm-up position. In contrast to the biceps brachii, it is able to do this in all positions of elbow flexion and extension. Supinator always acts together with biceps when the elbow joint is flexed.

Encircling the radius, supinator brings the hand into the palm-up position. In contrast to the biceps brachii, it is able to do this in all positions of elbow flexion and extension. Supinator always acts together with biceps when the elbow joint is flexed.

In unresisted forearm rotation, supinator is the most active muscle. However, under heavy loading, biceps becomes increasingly active with heavy loading. This means that strength training of supinator should be done at sub-maximal levels. This is definitely not a “no-pain, no gain” muscle and strength training should be done gradually and with care.

Supination strength decreases by two-thirds if the supinator muscle is surgically removed or disabled by disease or injury.

There is a delicate interplay between the supinator, brachialis, biceps brachii, and brachioradialis muscles during loaded flexion at the elbow.

Supinator consists of two planes of fibers. The superficial plane is almost just a flat tendon. The deeper plane is muscular. The deep branch of the radial nerve runs between them, allowing supinator TrPs to entrap the nerve.

The two planes arise in common from the supinator crest of the ulna, the lateral epicondyle of humerus, the radial collateral ligament, and the annular radial ligament.

The superficial fibers surround the upper part of the radius and are inserted into the lateral edge of the radial tuberosity, nearly halfway down the length of the bone. The upper fibers of the deeper plane form a sling-like bundle, encircling the neck of the radius; the greater part of this portion of the muscle is inserted into the top and outside surfaces of the body of the radius, closer to the top.

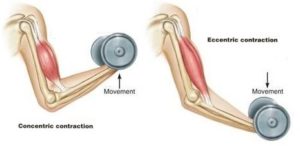

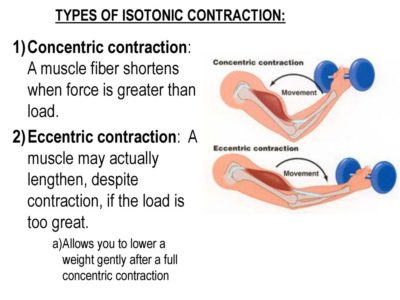

For example, in a biceps curl, you would use a concentric contraction of your biceps, coupled with an eccentric contraction of your triceps, to flex your elbow and push the weight up. As you lower the weight, eccentric contractions of your biceps are required to maintain control and prevent dropping the weight.

For example, in a biceps curl, you would use a concentric contraction of your biceps, coupled with an eccentric contraction of your triceps, to flex your elbow and push the weight up. As you lower the weight, eccentric contractions of your biceps are required to maintain control and prevent dropping the weight.

Isotonic Contractions

Isotonic contractions maintain constant tension in the muscle as the muscle changes length. This can occur only when a muscle’s maximal force of contraction exceeds the total load on the muscle. Isotonic muscle contractions can be either concentric (muscle shortens) or eccentric (muscle lengthens).Concentric Contractions

A concentric contraction is a type of muscle contraction in which the muscle shortens while generating force. This is typical of muscles that contract due to the sliding filament mechanism, and it occurs throughout the muscle. Such contractions also alter the angle of the joints to which the muscles are attached. This occurs throughout the length of the muscle, generating force; causing the muscle to shorten and the angle of the joint to change. For instance, a concentric contraction of the biceps would cause the arm to bend at the elbow as the hand moves close to the shoulder (a biceps curl).

A concentric contraction of the triceps would change the angle of the joint in the opposite direction, straightening the arm and moving the hand away from the shoulder.

This occurs throughout the length of the muscle, generating force; causing the muscle to shorten and the angle of the joint to change. For instance, a concentric contraction of the biceps would cause the arm to bend at the elbow as the hand moves close to the shoulder (a biceps curl).

A concentric contraction of the triceps would change the angle of the joint in the opposite direction, straightening the arm and moving the hand away from the shoulder.

Eccentric Contractions

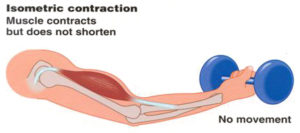

An eccentric contraction results in the lengthening of a muscle. These contractions decelerate muscles and joints (acting as “brakes” to concentric contractions) and can alter the position of the load force. During an eccentric contraction, the muscle lengthens while under tension due to an opposing force that is greater than the force generated by the muscle. However, rather than working to pull a joint in the direction of the muscle contraction, the muscle acts to decelerate the joint at the end of a movement or otherwise control the repositioning of a load. This can occur involuntarily (when attempting to move a weight too heavy for the muscle to lift) or voluntarily (when the muscle is “smoothing out” a movement). Strength training involving both eccentric and concentric contractions appears to increase muscular strength and joint stability more than training with concentric contractions alone.Isometric Contractions

In contrast to isotonic contractions, isometric contractions generate force without changing the length of the muscle. This is typical of muscles found in the hands and forearm: the muscles do not change length, and joints are not moved, so force for grip is sufficient. An example is when the muscles of the hand and forearm grip an object; the joints of the hand do not move, but muscles generate sufficient force to prevent the object from being dropped.

For people with hypermobile joints, strength training can be a challenge. Tension stresses the connective tissues of the joint as force is transmitted through its range of motion. Isometric exercises can be ideal in these circumstances because there is minimal movement. This means that the joint is placed into vulnerable hyperextended positions under force.

In contrast to isotonic contractions, isometric contractions generate force without changing the length of the muscle. This is typical of muscles found in the hands and forearm: the muscles do not change length, and joints are not moved, so force for grip is sufficient. An example is when the muscles of the hand and forearm grip an object; the joints of the hand do not move, but muscles generate sufficient force to prevent the object from being dropped.

For people with hypermobile joints, strength training can be a challenge. Tension stresses the connective tissues of the joint as force is transmitted through its range of motion. Isometric exercises can be ideal in these circumstances because there is minimal movement. This means that the joint is placed into vulnerable hyperextended positions under force. You can develop amazing strength without free weights, machines, or resistance bands.

One of the original bodybuilder gurus from the 1920s, Charles Atlas, based his workouts primarily on isometric exercises, eventually even trademarking a term for his exercise method that he called "Dynamic Tension."

If you have hypermobile joints you can strength train safely at home with isometric exercises.

You can develop amazing strength without free weights, machines, or resistance bands.

One of the original bodybuilder gurus from the 1920s, Charles Atlas, based his workouts primarily on isometric exercises, eventually even trademarking a term for his exercise method that he called "Dynamic Tension."

If you have hypermobile joints you can strength train safely at home with isometric exercises.