Rotator cuff injuries are a common cause of pain and disability among adults. Each year, almost 2 million people in the United States visit their doctors because of a rotator cuff problem. This might seem like a new problem but it isn’t. In generations past, rotator cuff problems were often referred to as “bursitis” of the shoulder and was very common.

Rotator cuff injuries are a common cause of pain and disability among adults. Each year, almost 2 million people in the United States visit their doctors because of a rotator cuff problem. This might seem like a new problem but it isn’t. In generations past, rotator cuff problems were often referred to as “bursitis” of the shoulder and was very common.

What Causes Rotator Cuff Injuries?

Most shoulder injuries occur in part because the underlying muscles are not working correctly. This contributes to dysfunction of the rotator cuff, degenerative labral tears, bone spurs and other shoulder problems.

These underlying muscular problems often trace back to improper body mechanics and other factors you can control. Some causes are hereditary. Some rotator cuff injuries happen suddenly to young, healthy people who have accidents.

Most muscular problems can be treated effectively with trigger point therapy and neuromuscular therapy. This approach restores function to the rotator cuff muscles, improves range of motion, reduces pain and improves strength.

Most muscular problems can be treated effectively with trigger point therapy and neuromuscular therapy. This approach restores function to the rotator cuff muscles, improves range of motion, reduces pain and improves strength.

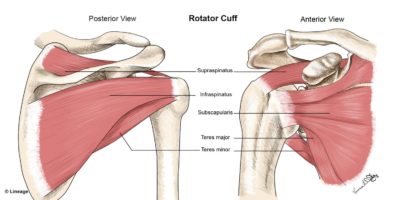

What is The Rotator Cuff?

Symptoms of rotator cuff injury can include shoulder pain, which is often worse with movement. A injured rotator cuff will also weaken your shoulder. This means that many daily activities, like getting dressed or washing, drying, brushing or combing your hair may become painful and difficult to accomplish.

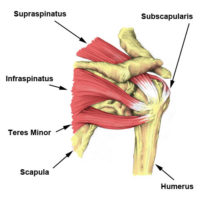

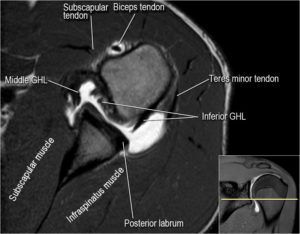

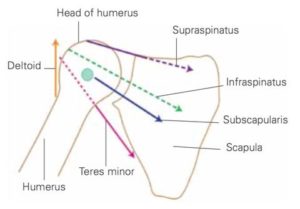

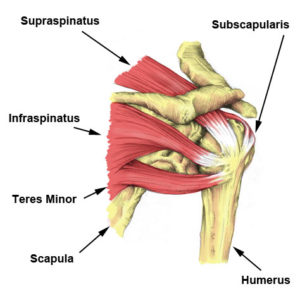

The rotator cuff is made up of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. The supraspinatus is the most commonly torn rotator cuff muscle.

Tears may occur suddenly or gradually over time. Risk factors include increasing age, certain repetitive activities, smoking, and a family history of the condition. Diagnosis is based on symptoms, examination, and medical imaging.

Treatment Options

Surgical approaches typically require 6-12 months of recovery and rehabilitation time. They have a fairly high initial success rate but it decreases with age and other risk factors. In addition, they also have a high long term failure rate that increases with age and other risk factors.

Surgical approaches typically require 6-12 months of recovery and rehabilitation time. They have a fairly high initial success rate but it decreases with age and other risk factors. In addition, they also have a high long term failure rate that increases with age and other risk factors.

Conservative treatment may include trigger point, neuromuscular and physical therapy, as well as anti-inflammatories and pain medication.

Conservative treatment may include trigger point, neuromuscular and physical therapy, as well as anti-inflammatories and pain medication.

Part of any effective therapy program involves identification and correction of poor body mechanics and other activities that perpetuate your pain.

If you are unable to raise your arm above 90 degrees after 2 weeks you should be further assessed.

Fortunately, conservative treatment such as trigger point therapy and neuromuscular therapy are as effective in most cases.

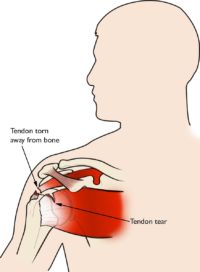

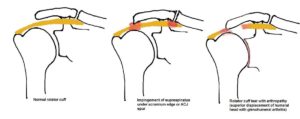

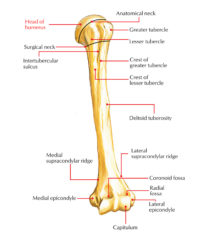

When one or more of the rotator cuff tendons is torn, the tendon no longer fully attaches to the head of the humerus.

Most tears occur in the supraspinatus tendon, but you can also tear other rotator cuff muscles. There are several other shoulder problems with similar symptoms.

In many cases, torn tendons begin by fraying. As the damage progresses, the tendon can completely tear, sometimes with lifting a heavy object.

There are different types of tears.

- Partial tear. This type of tear is also called an incomplete tear. It damages the tendon, but does not completely sever it.

- Full-thickness tear. This type of tear is also called a complete tear. It separates all of the tendon from the bone. With a full-thickness tear, there is basically a hole in the tendon.

There are a variety of ways to classify rotator cuff tears depending on size, shape, location and involvement of other structures in your shoulder.

The most common symptoms of a rotator cuff tear include:

- Pain when lifting and lowering your arm or with specific movements

- Pain at rest and at night, particularly if lying on the affected shoulder

- Weakness when lifting or rotating your arm

- Crepitus or crackling sensation when moving your shoulder in certain positions

Tears that happen suddenly, such as from a fall, usually cause intense pain. There may be a snapping sensation and immediate weakness in your upper arm.

Tears that develop slowly due to overuse also cause pain and arm weakness. You may have pain in the shoulder when you lift your arm, or pain that moves down your arm. At first, the pain may be mild and only present when lifting your arm over your head, such as reaching into a cupboard. Over-the-counter medication, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, may relieve the initial pain.

However, early conservative treatment, such as trigger point, neuromuscular or physical therapy is recommended to assess and treat your shoulder.

However, early conservative treatment, such as trigger point, neuromuscular or physical therapy is recommended to assess and treat your shoulder.

Over time, the pain may become more noticeable at rest, and no longer goes away with medications. You may have pain when you lie on the painful side at night. The pain and weakness in the shoulder may make routine activities such as combing your hair or reaching behind your back more difficult.

Some rotator cuff tears are not painful. However, these tears usually still result in weakness of your arm and other symptoms.

There are two main causes of rotator cuff tears: injury and degeneration.

Acute Tear

If you fall down on your outstretched arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking motion, you can tear your rotator cuff. This type of tear can occur along with other shoulder injuries, such as a broken collarbone or dislocated shoulder.

If you fall down on your outstretched arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking motion, you can tear your rotator cuff. This type of tear can occur along with other shoulder injuries, such as a broken collarbone or dislocated shoulder.

The key factors in these tears is that they are sudden and not necessarily preceded by other shoulder problems. A young football player tackled awkwardly or a person injured in a slip and fall are typical acute tears.

Degenerative Tear

Most tears are a chronic condition. It stems from the tendon wearing down slowly over time. This degeneration naturally occurs as we age but not everyone develops tears.

Most tears are a chronic condition. It stems from the tendon wearing down slowly over time. This degeneration naturally occurs as we age but not everyone develops tears.

However, a baseball pitcher who has mechanical errors in their throwing motion, prior untreated injuries or a genetic predisposition might development degenerative tears at young age.

Rotator cuff tears are more common in the dominant arm. However, if you have a degenerative tear in one shoulder, there is a greater chance of a rotator cuff tear in the opposite shoulder.

Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears.

- Repetitive stress. Repeating the same shoulder motions again and again can stress your rotator cuff muscles and tendons. Baseball, tennis, rowing, and weightlifting are examples of sports activities that can put you at risk for overuse tears. However, desk work and routine chores can cause overuse tears, as well.

- Lack of blood supply. As we get older, the blood supply in our rotator cuff tendons lessens. Without a good blood supply, the body’s natural ability to repair tendon damage is impaired. This can ultimately lead to a tendon tear.

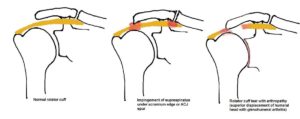

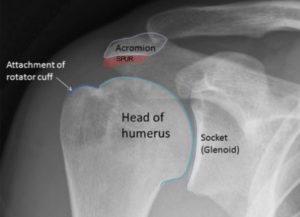

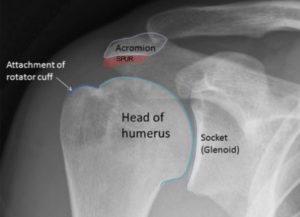

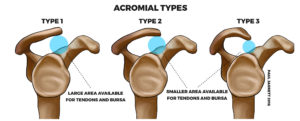

- Bony variations. The shape of the acromion varies and can be inherited. It is initially the same shape on both shoulders. The shape can change with overuse and injury. Curved and hooked shape acromions can impinge on a rotator cuff a tendon. This is called shoulder impingement syndrome. Over time it will weaken the tendon and make it more likely to tear.

- Bone spurs. As we age, bone spurs (bone overgrowth) often develop on the underside of the acromion bone. When we lift our arms, the spurs rub on the rotator cuff tendon. This is another type of shoulder impingement.

Risk Factors

Because most rotator cuff tears are largely caused by the normal wear and tear that goes along with aging, people over 40 are at greater risk.

People who do repetitive lifting or overhead activities are also at risk for rotator cuff tears.

Athletes are especially vulnerable to overuse tears, particularly tennis and volleyball players, swimmers and baseball pitchers.

Painters, electricians, plumbers, carpenters, and others who do overhead work also have a greater chance of developing tears.

Repetitive stress from poor body mechanics during office and desk work can also cause damage over time that leads to tears.

Studies strongly support an increased prevalence of rotator cuff tears as we age. In fact, those most prone to failed rotator cuff syndrome are people 65 years of age or older as well as those with large, sustained tears. Smokers, diabetes sufferers, individuals with muscle atrophy and/or fatty infiltration are at greater risk.

Studies strongly support an increased prevalence of rotator cuff tears as we age. In fact, those most prone to failed rotator cuff syndrome are people 65 years of age or older as well as those with large, sustained tears. Smokers, diabetes sufferers, individuals with muscle atrophy and/or fatty infiltration are at greater risk.

The frequency of rotator cuff tears increases steadily from less than 15% at about 50 to over 50% by the time we are in our 80’s. Yet, most people do not have obvious rotator cuff symptoms as they age.

Star atheletes getting rotator cuff surgery get a lot of attention but the actual incidence of rotator cuff injuries is lower in sports injuries or trauma than work and age related phenomena.

Star atheletes getting rotator cuff surgery get a lot of attention but the actual incidence of rotator cuff injuries is lower in sports injuries or trauma than work and age related phenomena.

Increased risk of rotator cuff tears is associated with a higher body mass index. Recurrent, awkward or off balance lifting and overhead motions increase our risk for rotator cuff injury. This includes triades that involve repetitive overhead work, such as carpenters, electricians, plumbers, painters, custodians, and servers.

People that competively play overhead sports such as swimming, water polo, volleyball, baseball, tennis, and American football quarterbacks are at a greater risk. Combat sports, such as mixed martial arts and boxing can cause severe rotator cuff injuries through overusing the shoulder by excessive practice. It is especially risky when punches miss their target.

People that competively play overhead sports such as swimming, water polo, volleyball, baseball, tennis, and American football quarterbacks are at a greater risk. Combat sports, such as mixed martial arts and boxing can cause severe rotator cuff injuries through overusing the shoulder by excessive practice. It is especially risky when punches miss their target.

Baseball pitchers and other throwers also at increased risk. Certain track-and-field activities, such as shot put, javelin throw are also of considerable risk, especially if you neglect warming-up or perform outdoors in cold weather. Proper warm-up of the throwing and/or swinging arm can help reduce the stress on the musculature of the shoulder girdle. Generally, the rates of rotator cuff injuries increases with age.

Corticosteroid injections around the tendons increases the risk of tendon tear and delay tendon healing!

Rotator Cuff Tear Treatment Options

A rotator cuff tear can be treated effectively without surgery. In fact, partial tears and some with complete tears will respond to conservative therapy. There is no benefit from operating sooner rather than later. Consequently, you can probably begin with nonsurgical management. However, early surgical treatment may be appropriate if you have a significant acute tears, or for young people with with full-thickness tears.

A rotator cuff tear can be treated effectively without surgery. In fact, partial tears and some with complete tears will respond to conservative therapy. There is no benefit from operating sooner rather than later. Consequently, you can probably begin with nonsurgical management. However, early surgical treatment may be appropriate if you have a significant acute tears, or for young people with with full-thickness tears.

In addition, post-surgery rehab takes about six months of intensive therapy anyway. In most cases, it is best to give a conservative approach a try first.

There does not appear to be any improvement in results with rotator-cuff surgery . Moreover, the failure rate over time of rotator cuff surgery is significant, especially in older populations. Because a conservative therapy approach has less complications and is less expensive it is recommended as the initial treatment. Conservative therapy is a good choice if you have pain but still have fairly well maintained function of your shoulder and arm.

Trigger Point Therapy

Traditional physical therapy can be very effective at rehab from rotator cuff injuries. However, the diagnosis of rotator cuff tear is tossed around pretty freely without adequate imaging or other testing. In addition, most physicians are unaware of the contributions of trigger points in the rotator cuff muscles in shoulder problems.

Traditional physical therapy can be very effective at rehab from rotator cuff injuries. However, the diagnosis of rotator cuff tear is tossed around pretty freely without adequate imaging or other testing. In addition, most physicians are unaware of the contributions of trigger points in the rotator cuff muscles in shoulder problems.

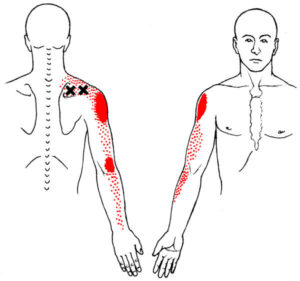

For example, the most common tear is in the tendon of the supraspinatus muscle. Trigger points in the supraspinatus muscle itself cause pain in shoulder that is almost identical to a rotator cuff tear. If also can also inhibit the muscle causing the weakness in raising your arm up to the side. This is the hallmark of a supraspinatus rotator cuff tear.

There are similar analogies for trigger points in the other rotator cuff muscles – infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor.

Traditional MRIs result in false positives, so unless an MR athrogram or skilled ultrasound assessment has clearly visualized the tear, it is difficult to know for sure if you have a rotator cuff tear.

Furthermore, the taut bands and dysfunction that of trigger points are probably part of a degenerative rotator cuff process to begin with. Identifying an inactivating trigger points in all rotator cuff and related muscles should be part of any treatment program.

Traditional Physical Therapy

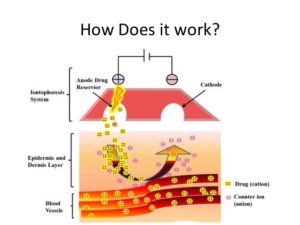

This includes medications that provide pain relief such as anti-inflammatory agents, topical pain relievers such as hot and cold packs. Physical therapy modalities, such as phonophoresis or iontophoresis use sound or electrical stimulation to deliver therapeutic medication through the skin into deeper tissues. Local anesthetic injections may be warranted. However, cortisone injections should not be used and can further damaged weakened tendons.

This includes medications that provide pain relief such as anti-inflammatory agents, topical pain relievers such as hot and cold packs. Physical therapy modalities, such as phonophoresis or iontophoresis use sound or electrical stimulation to deliver therapeutic medication through the skin into deeper tissues. Local anesthetic injections may be warranted. However, cortisone injections should not be used and can further damaged weakened tendons.

Early physical therapy may afford pain relief with modalities and help to maintain motion. Traditional ultrasound treatment does not work. As pain decreases, strength deficiencies and biomechanical errors can be corrected.

A conservative physical therapy program begins with preliminary rest and restriction from engaging in activities which gave rise to symptoms. Normally, inflammation can usually be controlled within one to two weeks, using a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as ibuprofen to decrease inflammation enough to make stretching tolerable. Rapid stiffening and increasing pain can result if sufficient stretching is not effective.

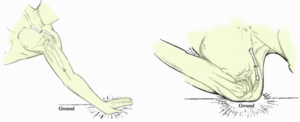

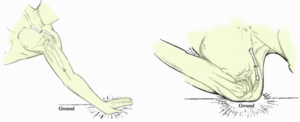

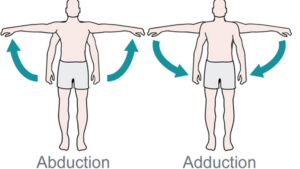

A gentle, passive range-of-motion program should be started to help prevent stiffness and maintain range of motion during this resting period. Exercises, for the front, lower, and rear shoulder, should be part of this program. Codman exercises (giant, pudding-stirring), to “permit the patient to abduct the arm by gravity, the supraspinatus remains relaxed, and no fulcrum is required” are widely used. However, before any rotator cuff strengthening can be started, the shoulder must have a full range of motion.

A gentle, passive range-of-motion program should be started to help prevent stiffness and maintain range of motion during this resting period. Exercises, for the front, lower, and rear shoulder, should be part of this program. Codman exercises (giant, pudding-stirring), to “permit the patient to abduct the arm by gravity, the supraspinatus remains relaxed, and no fulcrum is required” are widely used. However, before any rotator cuff strengthening can be started, the shoulder must have a full range of motion.

After a full, painless range of motion is achieved, you can advance to a gentle strengthening program. Rockwood coined the term orthotherapy to describe this program which is aimed at creating an exercise regimen that initially gently improves motion, then gradually improves strength in the shoulder girdle. This program involves a home therapy kit which includes elastic bands of different colors and strengths, a pulley set, and a three-piece, one-meter-long stick. The program is individually customized. Participants are asked to use their exercise program whether at home, work, or traveling.

After a full, painless range of motion is achieved, you can advance to a gentle strengthening program. Rockwood coined the term orthotherapy to describe this program which is aimed at creating an exercise regimen that initially gently improves motion, then gradually improves strength in the shoulder girdle. This program involves a home therapy kit which includes elastic bands of different colors and strengths, a pulley set, and a three-piece, one-meter-long stick. The program is individually customized. Participants are asked to use their exercise program whether at home, work, or traveling.

Corticosteroid injections around the tendons increases the risk of tendon tear and delay tendon healing!

Diagnosis is based upon physical assessment and your history, including symptoms, a description of prior injuries, occupational and sports activities and family history. A thorough physical examination of your shoulder includes visual inspection, range of motion evaluation, strength testing, palpation, tests to reproduce your symptoms, and neurological examination.

Diagnosis is based upon physical assessment and your history, including symptoms, a description of prior injuries, occupational and sports activities and family history. A thorough physical examination of your shoulder includes visual inspection, range of motion evaluation, strength testing, palpation, tests to reproduce your symptoms, and neurological examination.

Trigger points, disc problems and other issues with your neck can refer pain to your shoulder. The examination should include an assessment of the cervical spine looking for evidence suggestive of arthritis of the neck, a pinched nerve, or trigger points in the key neck muscles.

Tears of the rotator cuff tendon are described as partial thickness or full thickness, with or without complete detachment of the tendons from bone.

- Partial-thickness tears often appear as fraying of an intact tendon. These are sometimes referred to as grade 1 or stage 1 tears.

- Full-thickness tears are “through-and-through”. These tears can be small pinpoint, larger holes, or involve the majority of the tendon where it still remains attached to the humeral head. These are typically stage 2 tears.

- Full-thickness tears may also involve complete detachment of the tendon(s) from the humeral head and significantly dramatically impaired shoulder motion and function. Classically, these are stage 3 tears.

This approach to diagnosis is evolving. You can find more details on how rotator cuff tears are classified here.

For surgical purposes, tears are also described by location, size or area, and depth. Further subclasses include the acromial shape, degeneration or atrophy of muscles, tendon retraction, calcification and more. Age-related degeneration of thinning, disorientation and degeneration of the collagen fibers of the tendon and degenerative changes to cartilage surfaces in the joint are also considered.

For surgical purposes, tears are also described by location, size or area, and depth. Further subclasses include the acromial shape, degeneration or atrophy of muscles, tendon retraction, calcification and more. Age-related degeneration of thinning, disorientation and degeneration of the collagen fibers of the tendon and degenerative changes to cartilage surfaces in the joint are also considered.

Diagnostic imaging techniques include X-ray, MRI, MR arthrography, double-contrast arthrography, and ultrasound. Although MR arthrography is currently considered the gold standard, ultrasound may now be equally accurate at detecting tears.

Soft tissues like your rotator cuff do not show on X-rays. However, bone spurs, which can impinge upon the rotator cuff tendons, may be visible. Such spurs suggest chronic severe rotator cuff disease. Changes in positions of the head of your humerus may also be visible and suggest additional tests.

Soft tissues like your rotator cuff do not show on X-rays. However, bone spurs, which can impinge upon the rotator cuff tendons, may be visible. Such spurs suggest chronic severe rotator cuff disease. Changes in positions of the head of your humerus may also be visible and suggest additional tests.

Double-contrast arthrography involves injecting contrast dye into your shoulder joint to detect leakage out of the injured rotator cuff with initial fluoroscopy of the joint. Its reliability varies.

The most common diagnostic tool is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Sometimes this can indicate the size and location of the tear. MRI enables the detection or exclusion of complete rotator cuff tears with reasonable accuracy. Furthermore, it is also suitable to diagnose other pathologies of the shoulder joint.

The most common diagnostic tool is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Sometimes this can indicate the size and location of the tear. MRI enables the detection or exclusion of complete rotator cuff tears with reasonable accuracy. Furthermore, it is also suitable to diagnose other pathologies of the shoulder joint.

To diagnose partial tears and other joint disorders, MR arthography combines arthrography and MRI of the shoulder into two coordinated procedures.

Numerous studies has established that imaging, without clinical context, leads to diagnostic errors. Sound clinical judgement is essential in determining the cause of shoulder pain and or planning treatment. Imaging assists in clinical assessment and serves to confirm an initial diagnosis made by history and thorough physical exam. Over-reliance on imaging may lead to false positive results, overtreatment or distract from the actual problem causing your symptoms.

Benefits of surgery are unclear as of 2019. Even for full-thickness rotator cuff tears, conservative care (i.e., nonsurgical treatment) outcomes are usually reasonably good. Several instances when surgery may be recommended include:

Benefits of surgery are unclear as of 2019. Even for full-thickness rotator cuff tears, conservative care (i.e., nonsurgical treatment) outcomes are usually reasonably good. Several instances when surgery may be recommended include:

- 20 to 30-year-old active person with an acute tear and severe functional deficit from a specific event

- 30 to 50-year-old person with an acute rotator cuff tear secondary to a specific event

- a highly competitive athlete who is primarily involved in overhead or throwing sport

These individuals more often benefit from operative treatment because they are willing to tolerate the risks of surgery to return to their preoperative level of function, more willing to rehab thoroughly and have higher likelihood of a successful outcome.

Those who do not respond to, or are unsatisfied with, conservative treatment can seek a surgical opinion. A 2019 review found that the evidence does not support decompression surgery in those with more than 3 months of shoulder pain without a history of trauma.

Advances in arthroscopy now allow arthroscopic repair of even the largest tears, and arthroscopic techniques are now required to mobilize many retracted tears. The results match open surgical techniques, while permitting a more thorough evaluation of the shoulder at time of surgery. Arthroscopic surgery also allows for shorter recovery time although differences in postoperative pain or pain medication use are not seen between arthroscopic- and open-surgery.

When possible, surgeons make tension-free repairs in which they use grafted tissues rather than stitching to reconnect tendon segments. This can result in a complete repair. Other options are a partial repair, and reconstruction involving a bridge of biologic or synthetic substances. Partial repairs typically are performed on retracted cuff tears.

Repair of a complete, full-thickness tear involves tissue suture. The method currently in favor is to place an anchor in the bone at the natural attachment site, with resuture of torn tendon to the anchor. If tissue quality is poor, mesh may be used to reinforce the repair.

Repair of a complete, full-thickness tear involves tissue suture. The method currently in favor is to place an anchor in the bone at the natural attachment site, with resuture of torn tendon to the anchor. If tissue quality is poor, mesh may be used to reinforce the repair.

Tendon transfers are prescribed for young, active cuff-tear individual who experience weakness and decreased range of motion, but little pain. The technique is not considered appropriate for older people, or those with pre-operative stiffness or nerve injuries.

Contemporary techniques now use an all arthroscopic approach. Recovery can take as long as three–six months, with a sling being worn for the first one–six weeks. In the case of partial thickness tears, if surgery is undertaken, tear completion (converting the partial tear to a full tear) and then repair, is associated with better early outcomes than transtendinous repairs (where the intact fibres are preserved) and no difference in failure rates.

If a significant bone spur is present, surgery may include a subacromial decompression called an acromioplasty.

If a significant bone spur is present, surgery may include a subacromial decompression called an acromioplasty.

Although subacromial decompression may be beneficial in the management of partial and full-thickness tear repair, it does not repair the tear itself and arthroscopic decompression has more recently been combined with “mini-open” repair of the rotator cuff. The results of decompression alone tend to degrade with time, but the combination of repair and decompression appears to be more enduring. Subacromial decompression may not improve pain, function, or quality of life.

Biceps tenotomy and tenodesis are sometimes performed along with rotator cuff repair if you also have painful flexion of your shoulder. Tenodesis, which may be performed as an arthroscopic or open procedure, generally restores pain free motion in the biceps tendon, or attached portion of the labrum, but can cause pain. Tenotomy is a shorter surgery requiring less rehabilitation, that is more often performed in older patients, though after surgery there can be a cosmetic ‘popeye sign’ visible in thin arms.

People diagnosed with shoulder arthritis and rotator cuff dysfunction have the alternative of total shoulder replacement, if the cuff is largely intact or repairable. If the cuff is not repairable then a less durable reverse shoulder replacement is available.

Rehabilitation after surgery consists of three stages. First, the arm is immobilized so that the muscle can heal. Second, when appropriate, a therapist assists with passive exercises to regain range of motion. Third, the arm is gradually exercised actively, with a goal of regaining and enhancing strength. The empty can and full can exercises are amongst the most effective at isolating and strengthening the supraspinatus.

Rehabilitation after surgery consists of three stages. First, the arm is immobilized so that the muscle can heal. Second, when appropriate, a therapist assists with passive exercises to regain range of motion. Third, the arm is gradually exercised actively, with a goal of regaining and enhancing strength. The empty can and full can exercises are amongst the most effective at isolating and strengthening the supraspinatus.

Following arthroscopic rotator-cuff repair surgery, individuals need rehabilitation and physical therapy. Exercise decreases shoulder pain, strengthens the joint, and improves range of motion. Therapists design exercise regimens specific to the individual and their injury.

Traditionally, after injury the shoulder is immobilized for six weeks before rehabilitation. Most surgeons advocate using the sling for at least six weeks, though others advocate early, aggressive rehabilitation. The latter group favors the use of passive motion, which allows an individual to move the shoulder without physical effort. Alternatively, some authorities argue that therapy should be started later and carried out more cautiously. Theoretically, that gives tissues time to heal; though there is conflicting data regarding the benefits of early immobilization.

Individuals with a history of rotator cuff injury, particularly those recovering from tears, are prone to reinjury. Rehabbing too soon or too strenuously might increase the risk of retear or failure to heal. However, no research has proven a link between early therapy and the incidence of re-tears. In some studies, those who received earlier and more aggressive therapy reported reduced shoulder pain, less stiffness and better range of motion. Other research has shown that accelerated rehab results in better shoulder function.

There is consensus amongst orthopaedic surgeons and physical therapists regarding rotator cuff repair rehabilitation protocols. For approximately two to three weeks following surgery, an individual experiences shoulder pain and swelling; no major therapeutic measures are instituted in this window other than oral pain medicine and ice. Those at higher risk should be even more conservative with rehabilitations.

That is followed by the “proliferative” and “maturation and remodeling” phases of healing, which ensues for the following six to ten weeks. The effect of active or passive motion during any of the phases is unclear, due to conflicting information and a shortage of clinical evidence. Gentle physical therapy guided motion is instituted at this phase, only to prevent stiffness of the shoulder; the rotator cuff remains fragile.

At three months after surgery, physical therapy intervention changes substantially to focus on scapular mobilization and stretching of the shoulder joint.

Once full passive motion is regained (at usually about four to four and a half months after surgery) strengthening exercises are the focus. The strengthening focuses on the rotator cuff and the upper back/scapular stabilizers. Typically at about six months after surgery, most have made a majority of their expected gains.

Once full passive motion is regained (at usually about four to four and a half months after surgery) strengthening exercises are the focus. The strengthening focuses on the rotator cuff and the upper back/scapular stabilizers. Typically at about six months after surgery, most have made a majority of their expected gains.

The objective in repairing a rotator cuff is to enable an individual to regain full function. Surgeons and therapists analyze outcomes in several ways. Based on examinations, they compile scores on tests; some examples are those created by the University of California at Los Angeles and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons. Other outcome measures include the Constant score; the Simple Shoulder Test; and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand score. The tests assess range of motion and the degree of shoulder function.

Due to the conflicting information about the relative benefits of rehab conducted early or later, an individualized approach is necessary. The timing and nature of therapeutic activities are adjusted according to age and tissue integrity of the repair. Management is more complex in those who have suffered multiple tears.

Rotator Cuff Tear – More Details

Tears of the rotator cuff tendon are described as partial thickness or full thickness, with or without complete detachment of the tendons from bone.

Tears of the rotator cuff tendon are described as partial thickness or full thickness, with or without complete detachment of the tendons from bone.

- Partial-thickness tears often appear as fraying of an intact tendon. These are sometimes referred to a grade or stage 1 tears. Some severe partial thickness tears get classified as stage 2.

- Full-thickness tears are “through-and-through”. These tears can be small pinpoint, larger buttonhole, or involve the majority of the tendon where it still remains substantially attached to the humeral head and thus maintains function. These are typically stage 2 tears.

- Full-thickness tears may also involve complete detachment of the tendon(s) from the humeral head and may result in significantly impaired shoulder motion and function. These are stage 3 tears.

Some have promoted a different concept of three stages of rotator cuff disease. Stage I, occurs in those younger than 25 years and involves swelling and hemorrhage of the tendon and shoulder bursa. Stage II involves inflammation and early degenerative tears of the rotator cuff in 25- to 40-year-olds. Stage III involves tearing of the rotator cuff (partial or full thickness) and occurs in those older than 40 years.

Some have promoted a different concept of three stages of rotator cuff disease. Stage I, occurs in those younger than 25 years and involves swelling and hemorrhage of the tendon and shoulder bursa. Stage II involves inflammation and early degenerative tears of the rotator cuff in 25- to 40-year-olds. Stage III involves tearing of the rotator cuff (partial or full thickness) and occurs in those older than 40 years.

Shoulder pain is variable and may not be proportional to the size of the tear.

Full thickness rotator cuff tears are also classified by shape and size. These are common variations in supraspinatus tears. They are based on the shape of the tear. This system remains in common use.

Full thickness rotator cuff tears are also classified by shape and size. These are common variations in supraspinatus tears. They are based on the shape of the tear. This system remains in common use.

The issues of displacement of the head of the humerus and ‘retraction’ are often addressed.

In a different classification of subscapularis tears, we can also see This is the term used when the tendon seems to shrink, or retract, back towards the muscle. This complicates surgery because it is pulling it back will put it under tension. Currently, severe issues like this are usually handled with a tendon transfer to bridge the gap.

In a different classification of subscapularis tears, we can also see This is the term used when the tendon seems to shrink, or retract, back towards the muscle. This complicates surgery because it is pulling it back will put it under tension. Currently, severe issues like this are usually handled with a tendon transfer to bridge the gap.

There are other classification systems based on the location or size of the tear. In the Collin system, the tear is classified based on the location and extent of the tear.

First, the rotator cuff is divided into five components: supraspinatus; upper subscapularis; lower subscapularis; infraspinatus; and teres minor.  Rotator cuff tears classified by the involved components: type A, supraspinatus and superior subscapularis tears; type B, supraspinatus and entire subscapularis tears; type C, supraspinatus, superior subscapularis, and infraspinatus tears; type D, supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears; and type E, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tears.

Rotator cuff tears classified by the involved components: type A, supraspinatus and superior subscapularis tears; type B, supraspinatus and entire subscapularis tears; type C, supraspinatus, superior subscapularis, and infraspinatus tears; type D, supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears; and type E, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tears.

Rotator cuff tears are also sometimes classified based on the trauma that caused the injury:

- Acute, as a result of a sudden, powerful movement which might include falling onto an outstretched hand at speed, making a sudden thrust with a paddle in kayaking, or following a powerful pitch/throw

- Subacute, arising in similar situations but occurring in one of the five layers of the shoulder anatomy

- Chronic, developing over time, and usually occurring at or near the tendon (as a result of the tendon rubbing against the overlying bone), and often associated with an impingement syndrome

The shoulder is a complex mechanism involving bones, ligaments, joints, muscles, and tendons.

The shoulder is a complex mechanism involving bones, ligaments, joints, muscles, and tendons.

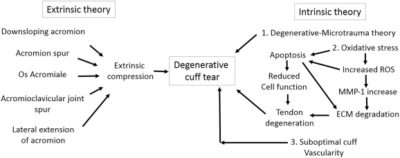

The two main causes are acute injury or chronic and cumulative degeneration of the shoulder joint. Mechanisms can be extrinsic, intrinsic or a combination of both.

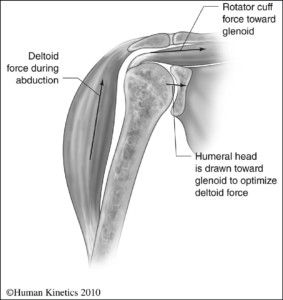

The cuff is responsible for stabilizing the shoulder joint to allow abduction and rotation of the humerus. When trauma occurs, these functions can be compromised. Because individuals are dependent on the shoulder for many activities, continued overuse can lead to tears, most often in the supraspinatus tendon.

The role of the supraspinatus is to resist downward motion, both while the shoulder is relaxed and carrying weight. Supraspinatus tears usually occurs at its insertion on the humeral head at the greater tubercle. Though the supraspinatus is the most commonly injured tendon in the rotator cuff, the other three can also be injured at the same time.

Trigger points in the supraspinatus and other rotator cuff muscles can cause similar pain. However, these trigger points can also inhibit these muscles and contribute to destablization and further injury of the joint.

Acute tears

The amount of stress needed to acutely tear a rotator cuff tendon will depend on the underlying condition of the tendon. If healthy, the stress needed will be high, such as with a fall on the outstretched arm. This stress may occur coincidentally with other injuries such as a dislocation of the shoulder.

The amount of stress needed to acutely tear a rotator cuff tendon will depend on the underlying condition of the tendon. If healthy, the stress needed will be high, such as with a fall on the outstretched arm. This stress may occur coincidentally with other injuries such as a dislocation of the shoulder.

In the case of a tendon with pre-existing degeneration, the force may be more modest, such as with a sudden lift, particularly with the arm above the horizontal position. The type of loading involved with injury is usually eccentric, such as removing a box that is too heavy from a shelf and trying to lower it in a controlled way as contracted muscles lengthen.

Chronic tears

Chronic tears are indicative of extended use in conjunction with other factors such as poor biomechanics or muscular imbalance. This includes poor desk posture and computer use. They are more common in the dominant arm, but a tear in one shoulder signals an increased risk of a tear in the opposing shoulder.

Chronic tears are indicative of extended use in conjunction with other factors such as poor biomechanics or muscular imbalance. This includes poor desk posture and computer use. They are more common in the dominant arm, but a tear in one shoulder signals an increased risk of a tear in the opposing shoulder.

Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears of which repetitive stress is the most significant. This stress consists of repeating the same shoulder motions frequently, such as overhead throwing, rowing, and weightlifting. Many jobs that require frequent shoulder movement such as lifting and overhead movements also contribute.

In older populations impairment of blood supply can also be an issue. With age, circulation to the rotator cuff tendons decreases, impairing natural ability to repair, increasing risk for tear. The reduction in circulation is one of the reasons smokers are at increased risk.

Another potential contributing cause is impingement syndrome, which occurs when the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles become irritated and inflamed while passing through the subacromial space beneath the acromion. This relatively small space becomes even smaller when the arm is raised in a forward or upward position. Repetitive impingement can inflame the tendons and bursa, resulting in this syndrome. The space is more narrow in some people naturally. Bone spurs can also make the area more vulnerable. Trigger points in key muscles can mimic impingement syndrome. Trigger points can also change the mechanics of the joint and contribute directly to impingement.

Another potential contributing cause is impingement syndrome, which occurs when the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles become irritated and inflamed while passing through the subacromial space beneath the acromion. This relatively small space becomes even smaller when the arm is raised in a forward or upward position. Repetitive impingement can inflame the tendons and bursa, resulting in this syndrome. The space is more narrow in some people naturally. Bone spurs can also make the area more vulnerable. Trigger points in key muscles can mimic impingement syndrome. Trigger points can also change the mechanics of the joint and contribute directly to impingement.

Extrinsic factors

Another important factor is the shape of the acromion, a bony projection from the scapula that curves over the shoulder joint. Hooked, curved, and laterally sloping acromia are strongly associated with cuff tears and may cause damage through direct traction on the tendon.

Another important factor is the shape of the acromion, a bony projection from the scapula that curves over the shoulder joint. Hooked, curved, and laterally sloping acromia are strongly associated with cuff tears and may cause damage through direct traction on the tendon.These differences in bony shape can be inherited. This is one reason that rotator cuff injuries may run in families. The shape of this important bone can also change based on the stresses and microtrauma it is subjected to.

Repetitive mechanical activities such as sports and exercise may contribute to flattening and hooking of the acromion. Cricket bowling, swimming, tennis, baseball, and kayaking are often implicated. Progression to a hooked acromion could be an adaptation to an already damaged, poorly balanced rotator cuff. Other anatomical factors include an os acromiale and bone spurs on the acromion.

Intrinsic factors

Intrinsic factors are injury mechanisms occurring within the rotator cuff itself. It is based on the degenerative-microtrauma model. This presumes that age-related tendon damage is compounded by chronic microtrauma. This results in partial tendon tears that can develop into full rotator cuff tears.

As a result of repetitive microtrauma in the setting of a degenerative rotator cuff tendon, inflammatory chemicals alter the local environment, and oxidative stress causes some tendon cells to die, leading to further rotator cuff tendon degeneration.

Another theory suggests neural overstimulation leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells and may also contribute to tendon degeneration.

The rotator cuff muscles are important in shoulder movements and in maintaining joint stability. These muscles arise from the shoulder blade (scapula) and connect to the head of the humerus, forming a ‘cuff’ around the shoulder joint. They hold the head of the humerus in the small and shallow socket of the scapula. The shoulder joint has been described as analagous golf ball sitting on a golf tee. This size discrepancy permits great freedom of movement of our arm at the shoulder. However, the inability of the ‘socket’ to fully seat the ‘ball’ makes the shoulder joint fundamentally unstable.

The rotator cuff muscles are important in shoulder movements and in maintaining joint stability. These muscles arise from the shoulder blade (scapula) and connect to the head of the humerus, forming a ‘cuff’ around the shoulder joint. They hold the head of the humerus in the small and shallow socket of the scapula. The shoulder joint has been described as analagous golf ball sitting on a golf tee. This size discrepancy permits great freedom of movement of our arm at the shoulder. However, the inability of the ‘socket’ to fully seat the ‘ball’ makes the shoulder joint fundamentally unstable.

During abduction of the arm, moving it outward and away from the trunk (torso), the rotator cuff compresses your shoulder joint, creating a fulcrum in order to allow the large deltoid muscle to further elevate the arm.

During abduction of the arm, moving it outward and away from the trunk (torso), the rotator cuff compresses your shoulder joint, creating a fulcrum in order to allow the large deltoid muscle to further elevate the arm.

In other words, without the rotator cuff, the humeral head would ride up partially out of the socket, lessening the efficiency of the deltoid muscle.

In other words, without the rotator cuff, the humeral head would ride up partially out of the socket, lessening the efficiency of the deltoid muscle.

It would also dislocate to the front and back. The front and back of the socket are more susceptible to shear force because these parts of the socket are as the top and bottom portions.

The rotator cuff’s contributions to compression into the socket and stability vary according to their stiffness and the direction of the force they apply upon the joint.

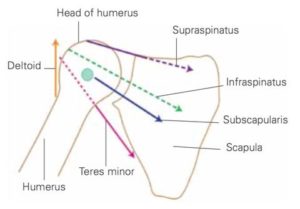

In addition to stabilizing the shoulder joint and controlling humeral head translation, the rotator cuff muscles also perform multiple other functions. These include abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation of the shoulder.

The infraspinatus and subscapularis have significant roles in elevating your arm up above the shoulder to the side (scaption), generating forces that are two to three times greater than the force produced by the supraspinatus muscle.

However, the supraspinatus is more effective for general shoulder abduction because of its moment arm and the location of its attachment to the humerus.

In anatomy, the rotator cuff is a group of muscles and their tendons that act to stabilize the shoulder and allow for its extensive range of motion. Of the seven shoulder muscles, four make up the rotator cuff. The four muscles are the supraspinatus muscle, the infraspinatus muscle, teres minor muscle, and the subscapularis muscle.

In anatomy, the rotator cuff is a group of muscles and their tendons that act to stabilize the shoulder and allow for its extensive range of motion. Of the seven shoulder muscles, four make up the rotator cuff. The four muscles are the supraspinatus muscle, the infraspinatus muscle, teres minor muscle, and the subscapularis muscle.

Rotator Cuff Attachments

The supraspinatus muscle spreads out in a horizontal band to insert on the superior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus (upper arm bone).

The supraspinatus muscle spreads out in a horizontal band to insert on the superior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus (upper arm bone).

The greater tubercle is a bony ‘bump’ on the outside head of the humerus. The infraspinatus and teres minor also attach here.

The lesser tubercle is the smaller bump at the top of your humerus that is closer to your body. The subscapularis muscle arises deep underneath your shoulder blade and its tendon attaches to here.

| Muscle | Origin on scapula | Attachment on humerus | Function |

| Supraspinatus muscle | supraspinous fossa | Upper facet of the greater tubercle | abducts the arm |

| Infraspinatus muscle | infraspinous fossa | Middle facet of the greater tubercle | externally rotates the arm |

| Teres minor muscle | middle half of lateral border | Lower facet of the greater tubercle | externally rotates the arm |

| Subscapularis muscle | subscapular fossa | lesser tubercle | internally rotates the arm |

Combined Attachment of Rotator Cuff Tendons

The four tendons of these muscles converge to form the rotator cuff tendon. These tendinous insertions along with the joint capsule, the coracohumeral ligament, and the glenohumeral ligament complex, blend into a united sheet of connective tissue before insertion into the greater and lesser tubercle.

The infraspinatus and teres minor fuse near their musculotendinous junctions, while the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons join as a sheath that surrounds the biceps tendon at the entrance of the bicipital groove. The supraspinatus is most commonly involved in a rotator cuff tear.